The business case for Indigenous business success in the NWT

We appreciate the opportunity to make the opening remarks in this issue of Aboriginal Business Quarterly. It has not been an easy year for many businesses, including Indigenous businesses, so this issue of ABQ that is focused on Indigenous procurement is timely.

A fundamental change to how procurement is managed for the benefit of Indigenous business is needed now more than ever, with active Indigenous involvement in developing and determining our economic priorities and strategies, especially in the use and development of our lands and resources that is beneficial to the NWT population and governments.

Nationally, Indigenous business is often overlooked, and in the Northwest Territories, where Indigenous people make up a relatively higher portion of the population than in all other Canadian jurisdictions except Nunavut, opportunities for Indigenous participation in the economy have been mainly limited to the support from the diamond industry.

To build upon the success that Indigenous business has experienced in the NWT, the territorial government (GNWT) must develop an Indigenous procurement policy. Many governments in Canada at the municipal, territorial, provincial, and national levels have developed already Indigenous procurement policies. Both Yukon and Nunavut have some form of Indigenous procurement policy, as does the federal government.

There is a direct correlation between the success of northern Indigenous business and the overall health of the territory’s economy. Currently, there is no easy way to measure the financial effect of Indigenous business on the local northern economies, but intuitively, we know that when money is spent with Indigenous companies, there is a significant multiplier effect. Indigenous communities across the North need money for investment in business expansion, housing, roads, education, and wellness programs. The profits generated by Indigenous businesses are put back into the economy in support of these needs.

We have already experienced the positive effects that Indigenous procurement has had on the NWT economy. The diamond mining industry provides a business case that proves a healthy Indigenous business sector drives a healthy economy.

The 2018 Diamond Mine report, published by the GNWT, documents 21 years (1996 – 2017) during which the active mines purchased almost $21 billion worth of goods and services. Of that amount, 70 percent, or $14.5 billion dollars, went to local NWT companies, and 31 percent, or $6.5 billion dollars, went to local Indigenous businesses. Clearly, local companies have benefited from the procurement practices that have been established by the mining industry, practices that are rooted in support for Indigenous business through each mining company’s Impact Benefit Agreements.

When Indigenous business is talked about, the assumption is often made that they only employ Indigenous people. This assumption is, of course, incorrect. While it is true that a mandate common to many Indigenous businesses is to employ their community members, the reality is that successful Indigenous businesses hire significant numbers of people from outside their community. Many Canadians would be surprised to learn that Indigenous businesses are incredibly inclusive, employing people from all walks of life.

The combined local workforces of Det’on Cho Management LP and Tłı˛cho˛ Investment Corporation represents the largest local employment in the NWT. When viewed together, they employ approximately the same number of NWT residents as the Diavik Mine, the Gahcho Kué Mine, and the Ekati Mine combined.

While some regions of the NWT have seen economic success, many remote communities have not, and have high levels of unemployment and little opportunity to build capacity. An Indigenous procurement strategy would help drive opportunities into remote communities and would provide true value for money to the GNWT by generating employment and job skills development, which are the building blocks of success.

If we are to be serious about economic reconciliation in Canada and the North, then Indigenous procurement must be a part of the strategy. Indigenous groups across the country are striving for independence and the ability to chart their futures. The more we can empower them to build successful businesses, the better off we all are as NWT residents, Northerners, and Canadians.

We hope you enjoy the feature on Indigenous procurement and hope that it will assist in generating meaningful conversations on the topic. Should you wish to speak with any of us on the topic of Indigenous procurement and Indigenous business, please feel free to reach us at the emails below.

Sincerely,

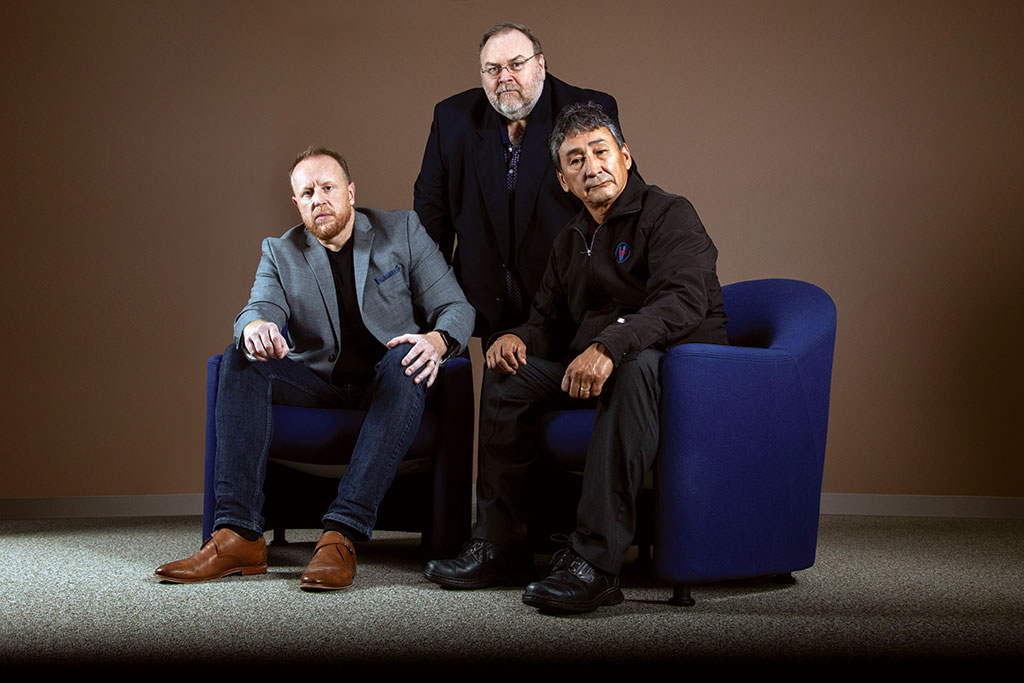

Mark Brajer, President and CEO Tlicho Investment Corporation

mbrajer@tlichoic.com

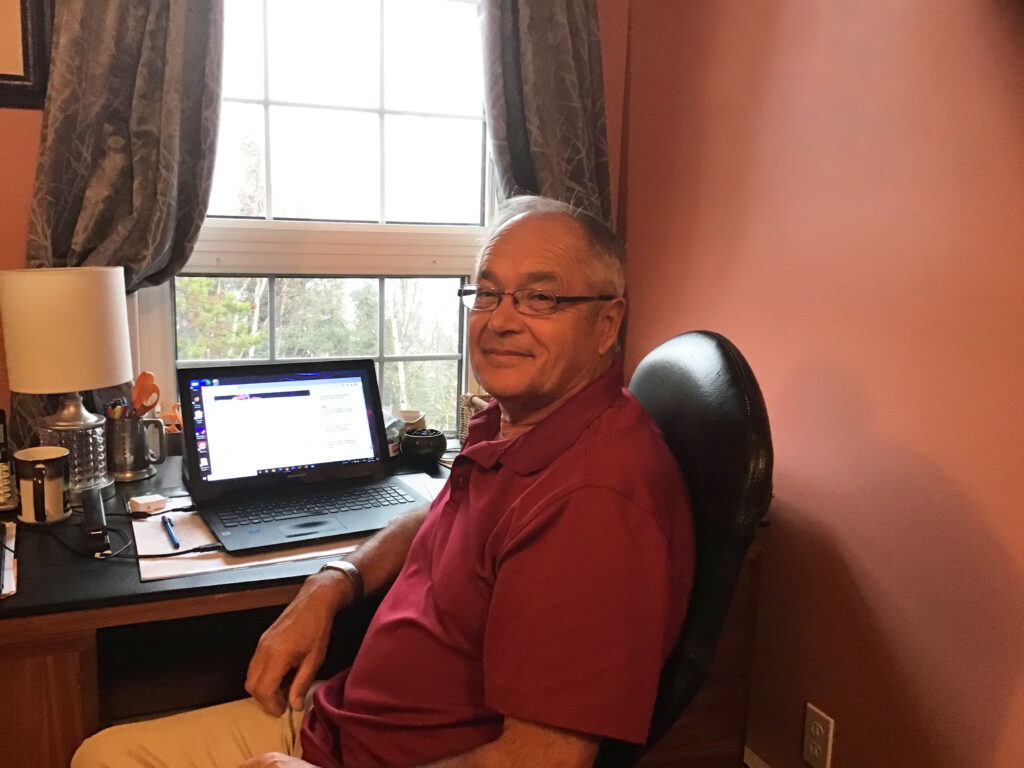

Paul Gruner, President and CEO Det’on Cho Management LP

paul@detoncho.com

Darrell Beaulieu, CEO Denendeh Investments Inc.

beaulieu@denendeh.ca

STICKY DOLLARS

Keeping government money at home in the NWT by making it stick to Indigenous businesses, communities and people

By: Bill Braden

It had all the makings of a great success story, shining proof that government was actually living up to decades of its own earnest promises to include First Nations in the NWT’s economy.

Instead, awarding a 10-kilometre road repair contract turned into a botched opportunity and a blizzard of protest that showed just how inflexible and uninformed the NWT Government is when it comes to making sensible, if not obligatory, spending decisions.

The government is “systematically discriminating against Tlicho people,” Grand Chief George Mackenzie said amongst other strongly-worded statements in mid-July when his government’s company, Tlicho Engineering & Environmental, lost its $3.498 million bid to rebuild the access road connecting the Tlicho community of Behchoko to Highway 3. The contract was awarded instead to RTL-Robinson Enterprise’s bid of $3.417 million – a mere $88,000 difference. (The 50-year old NWT firm is locally controlled but is one of several companies in the United States-based company Keenan Advantage Group.)

“This is our road. The Premier still chose not to work with us and refused to negotiate a contract,” Mackenzie told CBC Radio, after months of discussion about steering the work to the Tlicho. “Our Tlicho Agreement has commitments from GNWT to help people become self-sufficient, but the actions of the GNWT are working against us.”

Clearly embarrassed, GNWT called RTL and Tlicho leadership to see if there could be a way to salvage the fumble. It was grateful to get RTL’s commitment that it would ensure 25 percent of the jobs – about a dozen over three months – will go to Tlicho workers. (The original tender call did not require bidders to include any such local content.)

“We were happy to work with Tlicho on the project,” said RTL Construction’s Project Manager, Barry Henkel, in an email. “Throughout this summer’s construction projects we had already been employing Tlicho citizens…with or without the GNWT involvement on this project our plans were always to approach Tlicho Investment Corporation to hire as many people living in Behchoko as we could.”

“I am pleased that we have found a way to achieve that and move forward in our treaty relationship,” said Grand Chief Mackenzie in a joint news release in early August. “We took up the fight over this project because it is essential for our people to share in the wealth and economy of the NWT.”Premier Cochrane, in turn, stated again what past governments have always said: that it takes indigenous relations seriously, adding, “this agreement will ensure that there is a clear understanding of the GNWT’s approach to procurement in the region… which is consistent with Cabinet’s guiding principles.” Cochrane also made a firm commitment to directly negotiate contracts with Tłı˛cho˛ businesses for infrastructure located in their settlement region, or at minimum, to include Tlicho hiring and subcontracting in open tender calls.

Premier Cochrane explained during a media interview that because the project was partly federally funded, it was obliged to go through the conventional open tendering process.

“I call bulls**t to that,” said Darrell Beaulieu, CEO of Denendeh Investment Incorporated, a Dene Canadian corporation owned by all NWT First Nations. “The GNWT doesn’t have an Indigenous procurement strategy, but the federal government does. So, if they get federal dollars, they should be able to use federal policies to deliver and complete those projects…. the time to stop blaming the federal government. Even on the international front, at Canada’s request, USMCA has specific protections for Indigenous rights and this too is being overlooked by GNWT.” Article 32.5 of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) includes a general exception to protect Indigenous rights and clearly states that legal obligations to Indigenous peoples cannot be interfered with by commitments under trade rules. For Canada, this provides protection for the implementation of legal obligations affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act 1982, such as lands becoming subject to Indigenous title or rights, or obligations set out in modern treaties.

The GNWT procurement system, now managed by the Department of Finance, almost always focuses strictly on the bottom line, favouring low-cost outside suppliers and sidelining or ignoring treaty commitments, let alone the positive impact of flowing money through more northern workers’ pockets. “There are numerous examples of negotiated contracts between GNWT and Indigenous governments which could be replicated, there are existing Federal procurement policies and there are international rules. The GNWT comment that they must tender because of federal dollars and International Trade agreements has no standing. It was political will.” continued Beaulieu. The Tłı˛cho˛ road ruckus is a just one example of a chronic shortcoming in the GNWT’s approach to awarding contracts. When it looks only through the ‘value-for-money’ lens, it foregoes the far-reaching economic and social paybacks of government spending within its own borders. And there is a lot of room to try this out: in 2018-19, GNWT bought $348.9

million in goods and services but almost half of this, $161.4 million, was from companies listed as ‘not in NWT’ in the government’s report on expenditures for that year. The federal and some provincial governments, and even some cities, are reconciling this with developing their own specific Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP) that rests on the conviction that training First Nations labour, building organizational capacity, and strengthening local economies is worth the extra cash it will cost.

This is why a leading First Nations development corporation executive says the NWT government should have Indigenous procurement in its policy portfolio. Paul Gruner, President and CEO of Det’on Cho Management LP, the business arm of the Yellowknives Dene, is an experienced hand at Indigenous business affairs in Yukon and Alaska. He advocates a comprehensive approach, where government spending can and should be a way of enabling Indigenous ventures to become power houses for positive change at the local level. But it will take a major shift in political and bureaucratic thinking to get beyond that basic value-for-money mindset.

“We need to get educated on what the current Indigenous procurement policies and practices are,” says Gruner. “What are the gaps or the concerns? An external scan across the country for best practices, right? I think there’s also a lot we can learn as well from the current mining sector.”

Gruner acknowledges that value-for-money should always be a key consideration, but not the only one, even if it drives up the cost to government. “I think you have to ask how do you define value-for-dollar? It’s a balancing act. There has to be recognition that things cost more in the North.”

Gruner acknowledges that value-for-money should always be a key consideration, but not the only one, even if it drives up the cost to government. “I think you have to ask how do you define value-for-dollar? It’s a balancing act. There has to be recognition that things cost more in the North.”

Det’on Cho Management LP was started in 1988 to foster these kinds of business opportunities, and now employs 800 people which of 600 our Northern residents across 15 wholly owned companies and joint venture partnerships. Whenever possible Det’on Cho Management LP partners with local Northern companies as a way of to build capacity in First Nations, pointing to their Bouwa Whee Catering success story. Bouwa Whee Catering is the 2nd largest Indigenous owned camp catering company in Canada.

Bouwa Whee linked with a major southern camp services company almost 10 years ago, picked up contracts with emerging diamond mines, and as it built capacity and expertise, assumed full ownership. It’s a text-book success story, says Gruner, of how every partner has something to bring to the table. “Nobody should be scared about Indigenous business. Quite frankly, they should embrace it because we’re all going to win,” he says, when management and investment risks are shared.

Right -Darrell Beaulieu President and CEO of Denendeh Investments Incorporated

Behind – Mark Brajer Chief Executive Officer of Tłı˛cho˛ Investment Corporation

billbradenphoto

A Global, and Canadian, Movement to Indigenous Procurement

American civil rights movements of the 1960s fostered what may be the first such action anywhere, leading to the creation of the National Minority Supplier Diversity Council which recognized that long-neglected minority entrepreneurs deserved a place in its economy. https://nmsdc.org/

Canada currently spends about one percent of its overall procurement with indigenous-owned companies. Prompted by tough advocacy from the Canadian Council on Aboriginal Business (CCAB), the federal government has set an ambitious target of five percent of all federal buying. With its Supply Change™ system, CCAB is bringing government and corporate Canada on side. https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1554218527634/1554218554486

Australia, in 2008, set up the Australian Minority Supplier Diversity Council, based in the American model. (It later became Supply Nation, and in turn, became the model for Canada’s CCAB system). In 2015, Australia launched the country’s Indigenous Procurement Policy, with Supply Nation’s Indigenous Business Directory as the source for qualified businesses. Australia’s Northern Territory government is currently engaged in public consultation on its own Aboriginal Contracting Framework. https://supplynation.org.au/

Manitoba set out its Indigenous Procurement Initiative in 2016, to enable and promote more government trade with identified Indigenous suppliers. While it does not define any targets or bidding advantages, Manitoba bureaucrats have direction to look for projects, or portions of bigger jobs, that could be set aside for sole sourcing or even limit competition to only Indigenous businesses. https://www.gov.mb.ca/finance/psb/api/ab_proc.html

In a similar, almost simultaneous disappointment to the Tlicho road fiasco, the Yellowknives Dene First Nation (YKDFN) lost out this summer on a $20 million contract to develop baseline socio-economic, environmental and engineering research for the proposed Slave Geological Province Corridor. This transportation corridor would open up the mineral-rich region between Great Slave Lake and the Arctic Coast, a long-sought, road-to-resources vision shared by both Nunavut and the NWT – and the YKDFN. The Dene had spent months in 2019 negotiating a critical Memorandum of Understanding with GNWT that would forge a path for Dene inclusion in the development. While the Dene signed off on the deal, the GNWT didn’t – it was caught up in the three-month embargo the government imposed on signing new agreements prior to the November territorial election.

In the spring of 2020, GNWT issued contract calls for the work, funded in large part by the federal government, ignoring the provisions negotiated with the Dene. Regardless, they submitted a proposal in partnership with consulting firms Hemmera Envirochem and Dillon Engineering. In late July, the contract was awarded to southern-based Stantec and

Golder Associates.

The Dene slammed the decision and angrily withdrew their support for the Slave Geological Province Corridor. “In light of the GNWT’s questionable approach to engagement and disregard for supporting northern business, we are withdrawing our support,” said Chiefs Edward Sangris and Ernest Betsina in a joint August 1 press release. “Our support for major infrastructure projects will not be forthcoming until the current GNWT procurement policies are reviewed,” they declared, claiming the action “paralyzes growth prospects for Indigenous people.”

Later in August, during debate in the Legislative Assembly, Yellowknife Frame Lake MLA Kevin O’Reilly further condemned the government’s spending on the Slave Geological Province Corridor since 2015. “Shocking results from the Slave Geological Province road contracts over the last five years were tabled in the House in May,” he told the House. “Only four of 14 contracts went to northern contractors. Only three of the successful contractors were Business Incentive Policy-registered, and only 9 percent of the contracted amounts went to northern companies: $88,000 out of $987,000.”

While an Indigenous procurement policy would work to resolve issues such as these before they become contentious, drafting one is no small undertaking. Yukon is working on its own policy and is getting close to completing it, but it’s taken five years so far. There are big hurdles to overcome.

One ironic, and difficult, hurdle is that the northern private sector struggles to match the generous pay packets doled out by northern governments and big mining companies, but still must be competitive. Its bids are inevitably higher than the “helicopter” bidders from the south. So, when government only looks at a bid’s bottom line, who gets the contract?

The dilemma is plain. The cost of running a business, driven in part by government’s own employment and compensation model, squeezes northern bidders out of the field for government work. In Yukon, for example, the public sector makes 25 per cent more than the overall average income, resulting in what economists call “crowding out” for other sectors. Even northern bidders are sometimes tempted to contract lower cost southern labour, says Gruner, making their bids leaner and avoiding costly full-time payrolls. “If all that labour comes from down south, hypothetically speaking, is that success? No sticky dollars.”

Sticky dollars is a phrase Gruner loves to use, peppering his conversation with the notion that a “sticky” dollar sticks around the community: a resident worker can afford repairs to his home, pay taxes, buy a theatre ticket, support a volunteer project – instead of the welder from Saskatchewan who leaves little behind except the GNWT’s two per cent payroll tax

on earnings.

Another issue is the sense of private sector protectionism, as anxious business owners guard their turf against competition and shun collaboration. First Nations are just as prone to ‘silo-ing’ as anyone. “We need to get over or around our own protectionism and ‘silo mentality’, join forces amongst ourselves and see how much we can accomplish together,” urges Gruner.

Joe Handley, a former NWT premier and deputy minister of several departments over a long public sector career, backs that up. “Are we too comfortable in our own little silos – politically, financially – that we can’t join forces to get results that we will all benefit from? We’ve got to grow beyond that. Otherwise, we’re owned by someone else,” he says. Handley reflects that when he was deputy minister of Renewable Resources (now Environment and Natural Resources), they helped forge joint ventures between First Nations and firefighting helicopter companies, many of which are still active. “There was no requirement to do that, but we felt it was right to do that. Other departments didn’t view it that way… they always did business by tender,” Handley recalls. “There was no effort to involve Indigenous interests.”

He’s put his finger on a major underlying problem: there is no consistency across government in how to build tender calls and contracts amenable to Indigenous company involvement. And, while all of the land claims agreements co-signed by the GNWT have extensive language about economic inclusion, it’s often given short shrift.

“What’s happened over the last few years, with a lot of new bureaucrats, MLAs and ministers, people seem to be ignoring these economic opportunity chapters… the feeling is, well, that’s somebody else’s responsibility, not mine,” says Handley. Is government not in compliance with its own deals? “Yeah, in my view they aren’t. I doubt that very many of the people in the bureaucracy have even read the claims agreements,” Handley says. “I’d be surprised that even cabinet ministers or the Premier really understand the spirit and intent of what’s there… it’s almost as if, okay, we settled with those guys, now it’s back to business as usual. Those agreements changed the way we should be doing business here. It’s not just

being recognized.”

It’s widely held that the diamond industry in the 1990s set a new standard for how big corporations should reach out to the people whose riches they are harvesting. It was a new trend in high-level corporate governance, says Erik Madsen, a 34-year veteran of gold, iron and diamond mining across the Arctic. Their deals with First Nations were the right thing to do, says Madsen, and became gateways for getting mine licenses and permits.

“You can look at the sustainability policies of all the big companies. They all realize that the ways of mining in the past are long

gone. If you can’t demonstrate that you’re protecting the environment, you’re hiring local people, providing opportunity… the world will not allow mining to occur anymore. Sustainability is huge.”

It’s a scenario that doesn’t seem to apply to the government itself, he observes. “It’s sorta funny, that the government isn’t doing the same thing” with its own recent contract for the Tłı˛cho˛ access road to Behchoko. “The political outcry that they [stirred up] is unnecessary,” he says.

Madsen, who is now Lead, Corporate Affairs Canada with De Beers Group, says those early Impact Benefit Agreements (IBAs) and Socio-Economic Agreements (SEAs) help set up dozens of Indigenous corporations. The dollar numbers speak to the success these agreements produced. Since 1996, NWT diamond mines have spent about 70 percent, or $14.587 billion, of their total procurement in the north, says the GNWT 2018 report on the industry’s impact. More than a third of that, some $6.452 billion, was with Indigenous businesses. De Beers’ Gahcho Kué mine has IBA deals with six First Nations and Métis groups.

The GNWT’s only procurement policy is the BIP – Business Incentive Policy – which evolved from the first northern preference policies of the 1980s, “to keep carpet-bagging companies out of the NWT” recalls Nunavut Senator Dennis Patterson, who was then an Iqaluit MLA and cabinet minister in the NWT Legislative Assembly.

“Cabinet adopted criteria that northern resident ownership and senior management had to be located in the NWT,” he says. “That caused a sea change in some areas,” as it fostered the start-up of several services (he named architecture for one) that previously were only found outside of the North.

BIP, which was last updated in 2010, outlines cost advantages for resident bids. For contracts up to $1 million, it allows a 15 percent NWT and 5 percent local adjustment. For contracts over $1 million, the same applies to first $1 million, then dips to only 1.5 percent NWT and 0.5 percent local adjustment for the remainder, a consequence of interprovincial and international trade agreements Canada has signed on to. It applies to all GNWT departments and includes housing, medical and education authorities, but not municipalities.

“BIP has been studied by every government since it came about,” says Joe Handley. “It’s so difficult to get a consensus among those on the inside and on the outside of the registry. I remember trying… you get those who were already BIP’d trying to keep others out.”

The current Legislature has pegged its own BIP review as one of its 22 priorities, to start by mid-2020 and be ready for consideration sometime in 2022. It will look at what other jurisdictions are doing, said Todd Sasaki, a spokesperson for the Department of the Executive, by email. “As part of the GNWT’s mandate, procurement policies will be under review,” he confirmed.

Yukon IPP nearing completion

Building an Indigenous procurement policy (IPP) in Yukon has been in play for at least five years, and it’s still under review, said Albert Drapeau, Executive Director of the Yukon First Nations Chamber of Commerce.“

This is the first time the Yukon Government has worked with our First Nation governments to work on draft policy,” he says. The mandate to create an IPP came from the Yukon Forum, a political body of elected Yukon and First Nations leaders, directing that an Indigenous chapter be included in a major overhaul of Yukon government’s overall buying program.

That new umbrella policy was released late in 2019, but the Indigenous terms are still under closed negotiations between Yukon’s 14 First Nations and Yukon government officials, said Drapeau. “We understand [as of early August] drafting is almost complete for presentation to the territorial and First Nations governments, then it goes for public stakeholder review.” Drapeau anticipates it could be ready for adoption by late 2020 or early 2021.“

There is some uncertainty among the general business community,” he said “because they have not been involved in the discussions. And neither has our own Indigenous chamber of commerce.”

Yukon’s 2020-21 territorial budget came in at $1.62 billion (including a $4.1 million forecast surplus) and includes a hefty $369.7 million in capital spending. The budget will inject $130 million into Yukon’s construction industry, $23 million for housing, and $86 million for infrastructure, ranging from water and sewer upgrades to schools in Ross River and Burwash. It also earmarks $500,000 “to support entrepreneurial opportunities for Yukon First Nation development corporations.”

“Public procurement is complex and must balance preferential procurement policies with the principles of fair and transparent public procurement that considers the value of money,” said Sasaki. “The GNWT cannot commit to any changes… without first consulting signatories of land claims agreements, and we must meet our obligations under trade agreements.”

This BIP overhaul will have a wide audience indeed. The Standing Committee on Economic Development and the Environment, in a report tabled in the Legislature in June of this year, bolstered the desire to see more NWT-based spending that will enhance Indigenous commerce.

“Committee is urging the GNWT to implement more forward-thinking policies and services that more effectively support and develop capacity among NWT businesses,” says the report. “50.7 percent of the total population is Indigenous, and yet there is no specific policy in the NWT that supports the development of Indigenous businesses.” The Committee said a new BIP should “strengthen” Indigenous participation as prescribed in claims settlements with the Tlicho, Sahtu Dene and Métis, Gwich’in, Inuvialuit and other Métis groups.

The Committee stopped short of recommending adoption of an IPP but did target the bureaucracy as overdue for a major tune-up. “GNWT staff must understand NWT business capabilities better. Processes need to be established to ensure staff persons are seeking out, engaging and working collaboratively with NWT businesses, especially Indigenous businesses, in all competitive processes.”

Handley, while hopeful this review will work, is skeptical that with a closing date of 2022, it will make it to Cabinet’s table in time. “That’s just before the close of their term… and the same cycle will happen again. It will likely be dropped,” he predicts.

Darrell Beaulieu says Denendeh Investment Corporation has raised the need for a made-in-NWT IPP many times over the years and is ramping up its campaign to get it. “This past winter, a coalition of Indigenous leaders gathered, consisting of Dene, Métis and Inuvialuit governments and corporations, to find ways to stimulate the economy. We want to do an analysis on the economy, on infrastructure gaps, and look, at where all the dollars are going? Where’s it coming from? And where are people spending it?

“If you’re gonna have an economy, money has got to circulate, and the high number of southern-based workers is robbing that from the NWT economy. “The corporate attitude is that it’s too hard to attract workers to live here” deterred by isolation, cost of living, and climate, Beaulieu says. “With that attitude, the North is never going to develop or have the capacity to lower the cost of living.”

Beaulieu is reflecting the shockwave De Beers and Dominion Diamond Corporation set off when, in 2016 and 2017, they shifted their Yellowknife headquarters to Calgary to take advantage of that city’s plummeting real estate values. It betrayed a trust that northerners had developed in these miners, which had seemed genuine in their northern partnerships.

Beaulieu is scornful of the existing BIP process, which even denied his Denendeh corporation’s application. Why? “We had to ensure all of my shareholders are living in the NWT, and we had to produce proof of residency. Indirectly, we’ve got over 17,000 shareholders in the NWT… how am I going to do that? So Denendeh is not BIP’d. It’s more bureaucratic nonsense.”

Beaulieu reeled off examples of where Indigenous opportunities have not been maximized. They range from Denendeh Food Services Ltd losing a food supply deal for the Tłı˛cho˛ all season road project, to being shut out of a $58 million fuel supply contract in the NWT because, as a Deputy Minister told him, local NWT businesses doesn’t have the infrastructure and capacity.

“Does that mean no one is going to have the opportunity to build the infrastructure and capacity? Well, no, he said it’s a done deal… with that attitude that the deputy ministers have, how are we going to develop the capacity to do it ourselves? NWT Indigenous business have been hauling up here for years.”

Nunavut procurement policy embedded in 1993 final claim

Nunavut’s buying policies favouring local hire and buying are deeply embedded in Articles 23 and 24 of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act, which became law in 1993 and came into force in 1999. In 2000, a year after Nunavut was officially created, a new government agency, Nunavummi Nangminiqaqtunik Ikajuuti (NNI) began building the registry of eligible Inuit and Nunavut-based enterprises.

NNI’s lists are used by federal and Nunavut government buyers to assess bids, grading them according to price, location and ownership. In five per cent cost increments, bidders get preference for whether they are territorially and/or locally based. They get five percent more if they are at least 50 per cent Inuit-owned, an extra five for 75 per cent ownership, and a further five per cent if they are wholly Inuit-owned. Businesses have to update and apply every year to maintain their standing.

The system has evolved. It got a major independent review in 2013, and in 2017, a regulatory overhaul including a five-person tribunal to hear complaints.

The Inuit clearly take commitments made in their final agreement seriously. In 2003, Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., the Inuit claims oversight agency, filed a $1 billion lawsuit against Canada for failing to comply with contracting promises it made in the final claims agreement. They settled out of court, in 2015, for a hefty $255.5 million.

“I think Canada is coming around significantly to getting involved in honouring its land claim obligations in its tender obligations,” said Nunavut Senator Dennis Patterson in a phone interview. But he says the Nunavut Government itself lags, especially in the area of tightening up, and making more transparent, its registry protocols.

Mark Brajer, CEO of the Tlicho Investment Corporation, says First Nations shouldn’t be set up for failure by taking on big challenging contracts alone. But, he argues, “How about getting a piece of the action?” In his three years with Tlicho, Brajer says First Nations development corporations – whether big or small – get painted with the same brush by purchasers, who don’t always look at what their capacity really is.

“It’s disturbing to me that we have the skills and the people, but we get the short stick. That’s the challenge for us.” He urges outside bidders to seek out local and Indigenous partners. “It’s in their best interest to get local involvement, especially now, with the COVID crisis… it’s hard to get outside workers to come north.”

Like Gruner, Handley and Beaulieu, Brajer also promotes collaboration among First Nations. “We can be talking about a lot of leverage” by supporting each other, he says, citing the success of the joint venture between the Denesoline of Lutsel K’e, the Tlicho Investment Corporation, and Robinson Enterprises, which has built the southern section of the winter road to the diamond mines since 2016.

What will it take to get a made-in-NWT Indigenous Procurement Policy? It comes down to two words: political will. “The main thing to me is that you’ve got to have the government take control of this, and it’s got to start with the Premier and her key ministers,” says Handley. “The mandate is nobody’s, but it should be everybody’s. That’s why it has to start with the Premier.”

“There doesn’t seem to be the political will,” says Beaulieu, adding, “Not enough people are making the noise to say, look, after 50 years of GNWT, how come there’s no policy of our own? At the political level… the indigenous and business leadership has to be ruthless, to ensure that there’s an impact and relevance in the way that the GNWT is going to do business.”

“I say political will… among our elected (territorial) officials and of the indigenous groups across the territory,” says Gruner. “I think that’s where you’re going to start to see more ground swell among Indigenous groups, saying we need to review this, and we need to make a change.”

Gruner has high expectations for the recently convened Business Advisory Council, set up in June by then-Minister Nockleby to advise government primarily on how to restart the economy in the midst of the COVID pandemic. Gruner, who is deputy-chair, suggests the 17-member council can broaden its scope to better advance GNWT procurement practice, including pushing for an IPP.

An interim step toward a made-in-NWT policy, he suggests, could be to adopt the federal approach. “Let’s just take their criteria, apply that to everything we do on an interim basis while we craft something that works for us. Is that a realistic way to say to GNWT, okay, this is how we’re going to work?” ABQ

Canada free trade agreement (CFTA)

OVERVIEW OF THE AGREEMENT

In December 2014, federal, provincial and territorial governments began negotiations to strengthen and modernize the Agreement on Internal Trade (AIT). They were guided by direction from premiers and the federal government to secure an ambitious, balanced and equitable agreement that would level the playing field for trade and investment in Canada.

The new Canadian Free Trade Agreement (CFTA) resulted from these negotiations, entering into force on July 1st, 2017. It commits governments to a comprehensive set of rules that will help achieve a modern and competitive economic union for all Canadians.

Enhanced and modernized trade rules

The CFTA introduces important advancements to Canada’s internal trade framework that enhance the flow of goods and services, investment and labour mobility, eliminates technical barriers to trade, greatly expands procurement coverage, and promotes regulatory cooperation within Canada.

Comprehensive free trade rules

In contrast to the AIT, the CFTA’s rules apply automatically to almost all areas of economic activity in Canada, with any exceptions being clearly identified. This change enhances innovation as new goods and services such as the sharing economy, or clean technologies, are covered by rules designed to promote Canada’s long-term economic development.

The CFTA covers most of the service economy, which accounts for 70 per cent of Canada’s GDP. Coverage was extended to the energy sector for the first time, accounting for roughly nine per cent of Canada’s GDP.

Alignment with international obligations

The CFTA better aligns with Canada’s commitments under international trade agreements such as the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). This reduces compliance costs for Canadian firms who do business both at home and internationally.

Overall, the CFTA ensures that Canadian firms secure the same access to Canada’s market as that secured by firms from Canada’s international trading partners.

Government procurement that is more open to Canadian business. All governments have made precedent-setting commitments to promote open procurement practices. These commitments help create a level playing field for companies operating across Canada, and boost value-for-money in government purchasing.

For the first time, the energy sector and many energy utilities are covered by open procurement rules, resulting in more than $4.7 billion per year in procurement being opened up to broader competition.

Canadian companies that operate across a number of sectors, such as construction firms, are now able to compete more readily for government contracts.

Each government ensures that it has an independent bid protest mechanism in place, allowing suppliers to challenge procurements they think have broken the agreement’s rules.

Resolving regulatory barriers

Governments agreed to establish a regulatory reconciliation process to address regulatory differences across jurisdictions that act as a barrier to trade. The CFTA also introduces a mechanism to promote regulatory cooperation, which equips governments to develop common regulatory approaches for emerging sectors.

A survey by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business found that nearly one in three small businesses identified regulatory differences between jurisdictions as a significant barrier to internal trade.

The CFTA creates a senior-level Regulatory Reconciliation and Cooperation Table that helps address barriers to internal trade.

The CFTA’s new rules and processes pertaining to regulatory cooperation could help alleviate burdens by tackling regulatory differences in areas like the number of hours truckers can operate their vehicles in other provinces, the shipping of equipment across Canada, and trade in gasoline across the country.

Strengthened dispute settlement

The CFTA increases the maximum monetary penalties for governments that act in a manner that is inconsistent with the Agreement. Penalties vary based on population, but for example, the penalties for larger jurisdictions have doubled from a maximum of $5 million under the previous AIT to a maximum of $10 million under the new CFTA.

Protecting public policy objectives

Importantly, the CFTA preserves the ability of governments to adopt and apply their own laws and regulations for economic activity in the public interest in order to achieve public policy objectives. Such objectives include the protection of public health, social services, safety, consumer protection, the promotion and protection of cultural diversity and workers’ rights.

Promoting strengthened domestic trade in the future

The CFTA creates several forward-looking processes and working groups to help strengthen Canada’s economic union into the future. For example: It commits parties to establish a working group that assesses options for further liberalizing trade in alcohol. It triggers future negotiations on financial services, which account for roughly six per cent of Canada’s total GDP. There is also a commitment to enhance economic development in the food sector in the territories to address the cost and production of healthy food for territorial residents.

Economic impact

The CFTA works to enhance domestic commerce, a key driver of economic growth. Internal trade represents roughly one-fifth of Canada’s annual GDP, or the equivalent of around $385 billion per year. According to the Bank of Canada, removing interprovincial trade barriers could add up to two-tenths of a percentage point to

Canada’s potential output annually.

By lowering trade barriers, the CFTA also promotes productivity and encourages investment in Canadian communities. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has reported that Canada could raise its productivity by reducing non-tariff barriers through expansion of the AIT’s coverage and reconciliation of regulatory barriers. Further, the International Monetary Fund has indicated that lowering Canada’s interprovincial barriers to trade would help create the right conditions to expand domestic business investment and attract foreign direct investment.

www.cfta-alec.ca/canadian-free-trade–agreement/