Sharing Key to progress

IRC Shows Resource & Energy Sector a Path Forward

“The introduction of revenue sharing is more or less inevitable”

By John Curran

T

he year was 2011. Stephan Harper, armed with a shiny new majority government, proclaimed new pipelines would get built to tidewater. Nope. Fast forward to 2015 and Justin Trudeau’s sunny ways promised to end Alberta’s energy bottleneck blues. He may have bought a $4 billion project, but today in 2019 the current Prime Minister is no closer to building a pipeline than the last one got. In each case Aboriginal rights got in the way of expediency.

An Indian Resource Council (IRC) report titled First Nations Engagement in the Energy Sector in Western Canada perhaps shows a path forward for industry and the nation that has eluded federal leaders to date. Authored by Dr. Ken Coates, the essay says for the deadlock to be broken, First Nations and Metis groups must be engaged on several fronts, including: financially; through Impact and Benefit Agreements (IBAs); in terms of environmental protection; as part of collaborative infrastructure planning and development; and, to maximize training, jobs, and business opportunities.

“Canada stands to pay a substantial price in terms of employment and economic development if First Nations, oil and gas companies, pipeline firms and governments cannot identify a proper path forward,” states the IRC report. “The conditions are right for collaborative solutions, one based on respect for and understanding of Indigenous legal rights, hard-headed business decisions and the application of the highest international environmental standards.” While energy prices and demand are still near historical lows, the need for reaching suitable accommodations on all sides is no less important. For any solution to work, it must include resource revenue sharing the report argues.

Many Models Exist

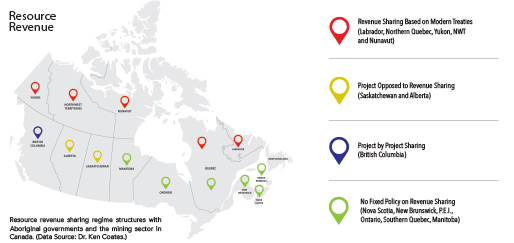

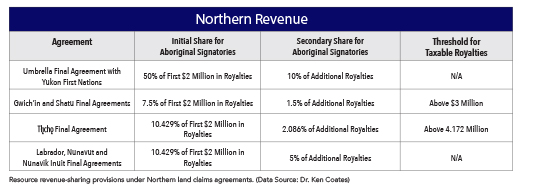

“Canada has a variety of resource revenue sharing regimes, from the structured and formal arrangements introduced in the Northwest Territories to the constitutionally protected systems imbedded in modern land claims treaties,” says the report. “British Columbia, long a laggard on engaging with Indigenous peoples on resource development, has established resource revenue sharing on mining and other resource projects, establishing arrangements with those First Nations closest to planned developments.”

In places where modern land claims have not yet delivered certainty, revenue sharing models are either under discussion (Manitoba and Ontario) or are being considered (the Maritime provinces).

“The Government of Alberta, as of 2015, has indicated a new openness to some form of revenue sharing, an approach that is likely to prove crucial in securing support for additional oil, gas and oil sands development and for the construction of new pipelines. Saskatchewan remains an outlier,” states the essay. “Resource revenue sharing has become a key feature of the Canadian resource economy and it is likely that it will be extended to the oil, gas and pipeline sector in due course.”

Dr. Coates explains that for First Nations and Metis people, revenue sharing is a financial acknowledgement of their ongoing relationship to the land, their treaty and Aboriginal rights, and the obligation of governments to ensure that Indigenous peoples benefit directly from the use of resources taken from their traditional territories.

“Revenue sharing also increases the own-source revenue going to First Nations communities, adding to their fiscal independence from government and providing an opportunity to chart their own economic path,” says the report.

“The introduction of revenue sharing is more or less inevitable, either as a percentage of government revenues earned from resource development (the option preferred by Indigenous groups and industry) or as an incremental payment from the resource companies (which some governments favour).

“It remains to be seen if this will happen voluntarily, as in the case of B.C., through agreements, [as in] the Yukon, enthusiastically, as in the Northwest Territories, cautiously (Manitoba and, potentially, Alberta) or reluctantly (Saskatchewan).”

The report insists there are ways to overcome the current stalemate, if all parties recognize their shared interests and appreciate the long-term value of positive and constructive relationships with First Nations and other Indigenous groups. “Without the enthusiastic and committed support and participation of affected First Nations, the chances of pipeline construction decline significantly,” concludes the IRC report. “First Nations groups along the pipeline corridor must support and embrace the final arrangements and be long-term partners in the projects. This reflects both the First Nations’ increased legal rights and the realities of community engagement and commitments made by the Government of Canada to respect Indigenous decisions. First Nations’ involvement must proceed in such a way that affected Aboriginal populations see tangible benefits in the form of genuine and long-term economic, social, and cultural progress and self-reliance that reduce dependence on transfer payments from the Government of Canada.”

The author does add a cautionary note about the need for Aboriginal groups to also make some concessions along the way as well. “The project must be financially feasible for the companies involved, including the pipeline operators and the oil sands firms. Otherwise any of the projects will wither and die,” writes Dr. Coates. “This happened with the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline project, much to the dismay of many Indigenous groups along the route that counted on the construction and maintenance jobs.” ABQ