Help Wanted & Needed

130,410 Workers Required to Support Mining Growth Through 2027

For resource-rich Canada, a healthy growing mining sector has always been part of our overall economic vigor and social stability.

While the benefits of that relative strength have not always found their way into Aboriginal communities, that’s likely all going to change going forward if you consider the findings of a pair of recent research projects conducted by the Mining Industry Human Resources Council (MiHR) and the Conference Board of Canada.

Now showing signs of recovery after almost a lost decade, this bedrock industry is about to face challenges with its labour supply. Massive challenges. In its report “Canadian Mining Labour Market Outlook 2017,” the MiHR reports that over the next 10 years, the resource sector will need to find up to 130,410 additional workers if it is going to continue expanding.

Already the signs are positive. The unemployment rate in mining dropped in the summer of 2016, from roughly 10 per cent to below 7 per cent where it has mostly remained during the first quarter of 2017.

“[That’s] a sign of early recovery for the sector, although a full recovery remains undeveloped at this time,” write the authors of the MiHR report. “MiHR’s hiring requirements forecast gauges the human resources efforts (i.e., “hiring effort”) that will be required to ensure the projected employment needs will be attained over time.”

According to industry estimates, the 10-year cumulative hiring requirements are estimated to be 87,830 workers under a baseline scenario; 130,410 workers in an expansionary scenario; and 43,200 workers in a contractionary scenario.

“One of the most significant challenges facing Canada’s mining industry is establishing a sustainable supply of labour that is able to withstand the economic volatility that characterizes the sector,” reports MiHR. “[The industry] anticipates critical gaps for various mining-related occupations, indicating that employers are expected to struggle to find workers they are projected to need in the long-term, unless corrective collaborative actions are taken to manage the future availability of workers.”

Of particular concern are professional and physical science occupations as well as technical occupations. These are estimated to have among the largest of any occupational gaps.

“According to MiHR’s forecasts, the industry’s hiring requirement in these occupations is projected to be roughly 18,210 from 2018 to 2027; yet, mining is only expected to secure about 8,670 new entrants over the same time, representing a gap of about 9,540 people, or about 52 per cent of all vacancies that are projected to remain unfilled,” states the report. “This poses a significant risk to mining operations, given that a thin labour supply has the potential to derail projects, drive up the cost of finding workers and ultimately undermine an operation’s ability to run competitively.”

Four Key Barriers

The report calls on all mining stakeholders – employers, government, educators and associations – to recognize they have a vested interest in managing this supply of labour, especially in the longer term. It highlights several barriers the industry must overcome on this front.

Age & Retirement – Canada’s aging population continues to have a significant impact on the mining workforce. Older workers have surged from 11 per cent in 2007 to 16 per cent in 2016, while younger workers have dropped from 13 per cent to 5 per cent over that same period. The exit of the Baby Boomers from the working world is expected to fuel the largest part of the coming demand with some 47 per cent of future openings related to the replacement of retiring workers.

“The replacement of a retiring worker can be a significant burden to employers,” notes the MiHR. “Each retiree takes with them a unique set of skills and knowledge, and those leaving with experience create a void that is difficult to fill. As a result, the incoming generations of new entrants are vitally important to the health of mining’s future labour supply, especially prospective students.”

Lack of Diversity – Diverse groups such as women and Aboriginal people continue to be under-represented in the mining labour force. For example, while women represent nearly half of the Canadian labour force, they make up only about 19 per cent of the labour force in mining.

Economic Volatility – Mining is characteristically volatile and is subject to corrections in commodity prices, production levels and employment. Both economic downturns and upswings result in widely fluctuating demand for labour and this instability can lead to major challenges that affect a mining employer’s ability to secure a robust supply of labour.

Remoteness – Mining operations often exist in remote parts of the country and in areas with extremely low populations lacking either the critical mass and/or the work-readiness skills to support a local labour market.

Given all of these factors, it has been common practice for employers to source workers from other regions of Canada and pay significant costs to transport them back and forth between the job site and home. But with those traditional pools of labour drying up, it could be good news for Aboriginal communities and the North on the whole.

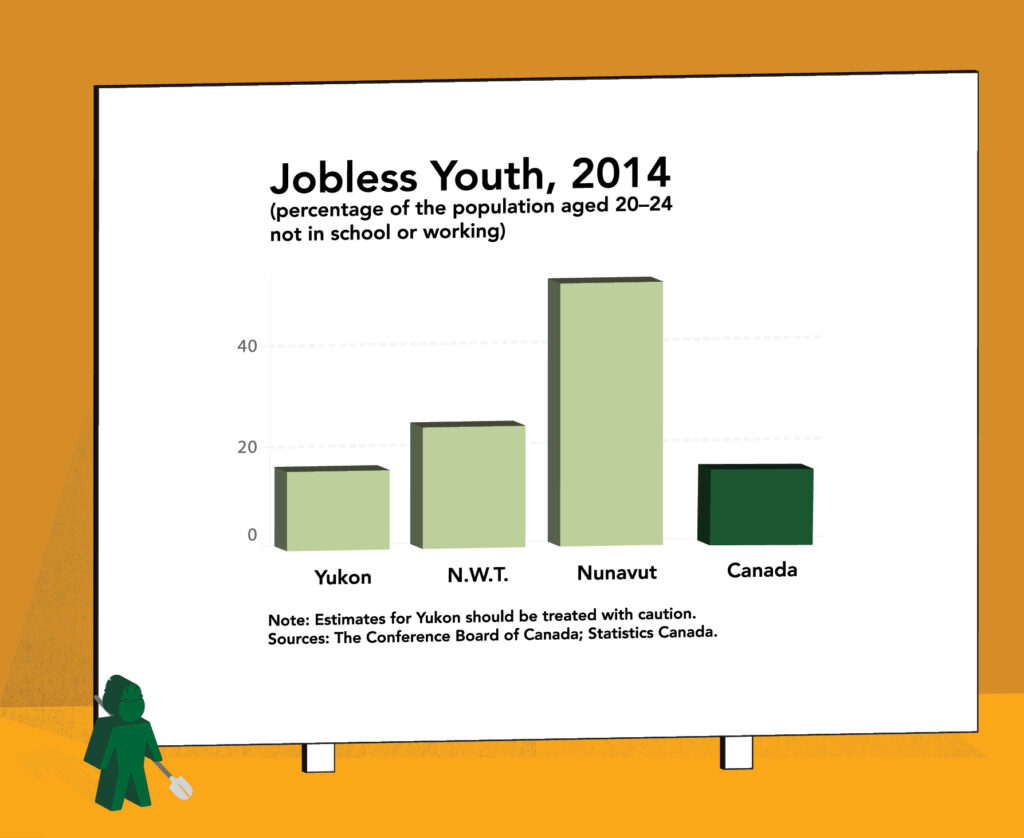

In its recent report “How Canada Performs,” the Conference Board of Canada examined social outcomes in the Territories and found that Yukon, NWT and Nunavut generally fall behind the Canadian average on measures of equity and social cohesion for a variety of reasons.

“For example, the vast distances between many communities can be a barrier to individuals seeking post-secondary education, which then affects their ability to obtain higher-skilled employment,” writes the Conference Board. “This, in turn, can affect rates of labour market participation and, consequently, unemployment – an important indicator of social outcomes.”

The report also noted that while the overall population of the territories is small, it includes substantial Indigenous populations that face distinct historical, cultural, and socio-economic challenges, including the impacts of residential schools. It stressed that although culturally diverse, First Nation, Métis, and Inuit populations in Canada share demographic features that distinguish them from non-Indigenous populations.

“Notably, the Indigenous populations of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut are much younger than the Canadian average, and the Indigenous populations of the territories make up about 51 per cent of the population North of 60,” the Board reports.

So with its youthful, underemployed population located in the same remote areas the resource sector operates in, it’s clear there is a new potential labour supply just waiting for the mines of tomorrow: Canada’s Indigenous population.

The Conference Board also highlighted a key barrier keeping this matching of demand and supply from coalescing in Canada’s hinterland and it’s a familiar refrain, the lack of educational attainment.

“The availability and accessibility of relevant education and skills training can have significant effects on both equity and social cohesion,” writes the Conference Board.

It points out that while post-secondary institutions – such as Yukon College, Aurora College, and Nunavut Arctic College – do give people some options in the territories to further their education, problems remain since students in remote communities may have to fly to larger population areas to access such opportunities.

“Post-secondary educational attainment has generally been improving in the territories, but except for Yukon, it is still lower than the national average,” writes the Board. “As of 2011, the most recent year of available data, Yukon leads the territories and the national average, with 67.1 per cent of adults aged 25 to 64 having completed a post-secondary certificate, diploma, or degree. The NWT, at 59.3 per cent of the population with post-secondary qualifications, falls slightly below the national average of 64.1 per cent. In Nunavut, only 41.6 per cent of adults have completed some form of post-secondary education.”

For resource-rich Canada, a healthy growing mining sector has always been part of our overall economic vigor and social stability.

While the benefits of that relative strength have not always found their way into Aboriginal communities, that’s likely all going to change going forward if you consider the findings of a pair of recent research projects conducted by the Mining Industry Human Resources Council (MiHR) and the Conference Board of Canada.

Now showing signs of recovery after almost a lost decade, this bedrock industry is about to face challenges with its labour supply. Massive challenges. In its report “Canadian Mining Labour Market Outlook 2017,” the MiHR reports that over the next 10 years, the resource sector will need to find up to 130,410 additional workers if it is going to continue expanding.

Already the signs are positive. The unemployment rate in mining dropped in the summer of 2016, from roughly 10 per cent to below 7 per cent where it has mostly remained during the first quarter of 2017.

“[That’s] a sign of early recovery for the sector, although a full recovery remains undeveloped at this time,” write the authors of the MiHR report. “MiHR’s hiring requirements forecast gauges the human resources efforts (i.e., “hiring effort”) that will be required to ensure the projected employment needs will be attained over time.”

According to industry estimates, the 10-year cumulative hiring requirements are estimated to be 87,830 workers under a baseline scenario; 130,410 workers in an expansionary scenario; and 43,200 workers in a contractionary scenario.

“One of the most significant challenges facing Canada’s mining industry is establishing a sustainable supply of labour that is able to withstand the economic volatility that characterizes the sector,” reports MiHR. “[The industry] anticipates critical gaps for various mining-related occupations, indicating that employers are expected to struggle to find workers they are projected to need in the long-term, unless corrective collaborative actions are taken to manage the future availability of workers.”

Of particular concern are professional and physical science occupations as well as technical occupations. These are estimated to have among the largest of any occupational gaps.

“According to MiHR’s forecasts, the industry’s hiring requirement in these occupations is projected to be roughly 18,210 from 2018 to 2027; yet, mining is only expected to secure about 8,670 new entrants over the same time, representing a gap of about 9,540 people, or about 52 per cent of all vacancies that are projected to remain unfilled,” states the report. “This poses a significant risk to mining operations, given that a thin labour supply has the potential to derail projects, drive up the cost of finding workers and ultimately undermine an operation’s ability to run competitively.”

Four Key Barriers

The report calls on all mining stakeholders – employers, government, educators and associations – to recognize they have a vested interest in managing this supply of labour, especially in the longer term. It highlights several barriers the industry must overcome on this front.

Age & Retirement – Canada’s aging population continues to have a significant impact on the mining workforce. Older workers have surged from 11 per cent in 2007 to 16 per cent in 2016, while younger workers have dropped from 13 per cent to 5 per cent over that same period. The exit of the Baby Boomers from the working world is expected to fuel the largest part of the coming demand with some 47 per cent of future openings related to the replacement of retiring workers.

“The replacement of a retiring worker can be a significant burden to employers,” notes the MiHR. “Each retiree takes with them a unique set of skills and knowledge, and those leaving with experience create a void that is difficult to fill. As a result, the incoming generations of new entrants are vitally important to the health of mining’s future labour supply, especially prospective students.”

Lack of Diversity – Diverse groups such as women and Aboriginal people continue to be under-represented in the mining labour force. For example, while women represent nearly half of the Canadian labour force, they make up only about 19 per cent of the labour force in mining.

Economic Volatility – Mining is characteristically volatile and is subject to corrections in commodity prices, production levels and employment. Both economic downturns and upswings result in widely fluctuating demand for labour and this instability can lead to major challenges that affect a mining employer’s ability to secure a robust supply of labour.

Remoteness – Mining operations often exist in remote parts of the country and in areas with extremely low populations lacking either the critical mass and/or the work-readiness skills to support a local labour market.

Given all of these factors, it has been common practice for employers to source workers from other regions of Canada and pay significant costs to transport them back and forth between the job site and home. But with those traditional pools of labour drying up, it could be good news for Aboriginal communities and the North on the whole.

In its recent report “How Canada Performs,” the Conference Board of Canada examined social outcomes in the Territories and found that Yukon, NWT and Nunavut generally fall behind the Canadian average on measures of equity and social cohesion for a variety of reasons.

“For example, the vast distances between many communities can be a barrier to individuals seeking post-secondary education, which then affects their ability to obtain higher-skilled employment,” writes the Conference Board. “This, in turn, can affect rates of labour market participation and, consequently, unemployment – an important indicator of social outcomes.”

The report also noted that while the overall population of the territories is small, it includes substantial Indigenous populations that face distinct historical, cultural, and socio-economic challenges, including the impacts of residential schools. It stressed that although culturally diverse, First Nation, Métis, and Inuit populations in Canada share demographic features that distinguish them from non-Indigenous populations.

“Notably, the Indigenous populations of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut are much younger than the Canadian average, and the Indigenous populations of the territories make up about 51 per cent of the population North of 60,” the Board reports.

So with its youthful, underemployed population located in the same remote areas the resource sector operates in, it’s clear there is a new potential labour supply just waiting for the mines of tomorrow: Canada’s Indigenous population.

The Conference Board also highlighted a key barrier keeping this matching of demand and supply from coalescing in Canada’s hinterland and it’s a familiar refrain, the lack of educational attainment.

“The availability and accessibility of relevant education and skills training can have significant effects on both equity and social cohesion,” writes the Conference Board.

It points out that while post-secondary institutions – such as Yukon College, Aurora College, and Nunavut Arctic College – do give people some options in the territories to further their education, problems remain since students in remote communities may have to fly to larger population areas to access such opportunities.

“Post-secondary educational attainment has generally been improving in the territories, but except for Yukon, it is still lower than the national average,” writes the Board. “As of 2011, the most recent year of available data, Yukon leads the territories and the national average, with 67.1 per cent of adults aged 25 to 64 having completed a post-secondary certificate, diploma, or degree. The NWT, at 59.3 per cent of the population with post-secondary qualifications, falls slightly below the national average of 64.1 per cent. In Nunavut, only 41.6 per cent of adults have completed some form of post-secondary education.”

It theorizes that reducing the educational gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals will benefit everyone in society, as education serves as a ladder to upward social mobility.

“A focus on early-childhood development programs, particularly for disadvantaged children, for example, the NWT’s kindergarten programs that focus on fostering a sense of identity in addition to developing the basics of reading, writing, and mathematics, as well as initiatives like the NWT’s Skills for Success, which aims to reduce education gaps, will help improve social outcomes in the future.”

Once that happens, matching the labour needs of the resource sector with social equity needs of Indigenous communities will result in a win-win situation for the entire country and the North in particular.