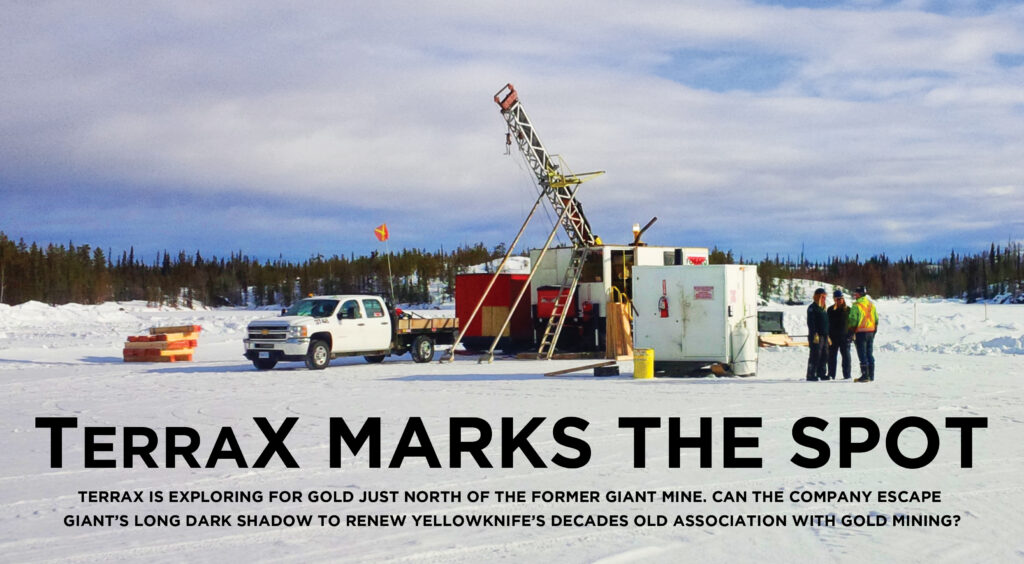

TerraX Marks the Spot

By Beverly Cramp

At first glance, the old-fashioned binders lying on a table in the Geoscience Centre in Yellowknife belied the potential for future treasure. But it didn’t take experienced mining professionals like Joe Campbell and Tom Setterfield very long to see that the information contained within this archival material from the old Giant Mine could lead to something big.

It was January 2013 and Campbell and Setterfield were on the hunt for data to support a decision to buy mineral leases to the immediate north of the property where Giant mined gold for nearly six decades. At the time of the archive search, the mineral leases were owned by Century Mining, in receivership because of financial difficulties at its mine in Quebec.

Campbell’s career as a professional geologist spans 34 years and several management and executive management positions with various companies including a large nickel project in Cuba, and more recently, as the project manager who took the Meliadine gold project near Rankin Inlet in Nunavut from discovery to pre-feasibility over a seven-year period. Campbell interested Agnico Eagle Mines (AEM) in Meliadine, which precipitated the company’s eventual purchase of the project. The Meliadine gold site is now one of AEM’s largest projects in terms of reserves and resources.

Campbell formed TerraX Minerals Inc. in 2007 and is the company’s president, and Setterfield is vice-president of exploration. Due to poor worldwide investment in the mining industry at that time, the new company was relatively inactive during its first several years. Then Campbell got wind of Century Mining’s asset sell-off, a company that he knew had a reputation for acquiring good ground.

Not wanting to gamble on reputation only, Campbell put in a bid to buy the leases on the condition that he and his Ottawa-based TerraX colleagues got a month to investigate before finalizing the sale. He didn’t expect the information would be so easy to come by.

“We went right to the horse’s mouth, to Yellowknife,” says Campbell. “Our first stop was the Geoscience Centre because they had preserved the archives of the Giant Mine when the old site was being torn down. We told them we were coming. Several of their employees are former geologists and scientists from the Giant and Con Mines. They had the information right there, laid out for us. Not all of it, but the heart of it. Right from

the get-go, as soon as I was shown the information in those old binders, I thought ‘okay I can see that lots of drilling was done’ and a high grade intersection jumped out at me.”

For Campbell, the due diligence was done. He knew right away they had something promising. Setterfield spent the next several months doing the hard work, gathering more information from the old drilling logs of 30,000 metres of drill core from the area known as Northbelt, located 15 kilometers north of Yellowknife. Not that anyone at TerraX was complaining about the amount of work that involved. All that historical drilling data was valuable and helped reduce the amount of TerraX’s own finances that needed to be spent on exploration drilling.

“It meant we already knew where those holes had been drilled on [Giant’s] adjacent property,” says Campbell. “When you factor in that it costs approximately $200 a metre to drill, all in, and add in the labour and time involved, that was the equivalent of having about $10-million fall into our laps because it gave us direct targets to start work on instead of having to scour the property,” Campbell says.

Upon completion of the deal to buy the Century Mining leases, Campbell began the job of raising money to begin pre-production. “It’s an ongoing business to raise money for the mine project,” he says adding that the historical drilling information made the job easier. “Our ability to raise funds is better than most other junior mining companies.”

The first two rounds of investment funding came in 2013 for a total of $3.6 million. Then another $2.8 million was raised last summer. Another founding member of TerraX, Vancouver-based Stuart Rogers, is chief financial officer and director, and has been working with the venture capital community in Vancouver since 1987. He specializes in early stage financing of resource projects through junior markets such as the TSX Venture Exchange, the Toronto Stock Exchange and NASDAQ Small Cap Market.

Rogers’ expertise is especially important to TerraX because, as Campbell notes, it will take 8-10 years, if everything goes smoothly, before an operating mine is feasible. “These things don’t happen very quickly in this business,” he says. “Our project will require several years of exploration. Then we’ll need a couple of years of pre-production work including base line studies, economic studies and so forth. Then we must go through a drawn-out approval process that allows every stakeholder to have a kick at the can.”

The historical significance of the Yellowknife Gold Belt, where Northbelt is located, greatly reduces risk and makes it that much easier for TerraX. “When you’re in an area of historical success your chances are that much better. We’re not re-inventing the wheel. Rather we’re following an old and tried and true pattern,” says Campbell noting that any geologist with knowledge of the area would be aware of the importance of the Yellowknife region.

With further land acquisitions, TerraX now controls over 9,000 hectares of contiguous land within the Yellowknife Gold Belt.

But there’s a negative side to so much history. After almost 60 years of continuous operations, many of them using old mining and waste disposal methods, the Giant mine site had become one of the worst contaminated sites in Canada. The mine owners at closing, Royal Oak Mines, declared bankruptcy and left the country, leaving a huge environmental liability for the federal government. A big part of that problem is the underground storage vaults containing deadly arsenic trioxide dust, a by-product of extracting gold from the mineral arsenopyrite ore. There are also contaminated buildings and soils on the old Giant site and a huge contaminated tailings pond. Site remediation is underway and will continue for decades. Estimated clean-up costs are close to a billion dollars.

How will this blighted historical baggage have an impact on the public’s perception of TerraX’s plans for a new gold mine in the Yellowknife area? Campbell is well aware of the problem, and said they flagged it from the very beginning as a major issue.

“I called it the albatross around our necks in terms of public perception. Our strategy was to face it straight up,” Campbell says. “We are not Giant Mine. We have no affiliation with them. Our activities and how we carry them out is completely different. The industry has made a quantum change since the 30s and 40s and 50s. Many of the previous two mines’ difficulties were from those early years.”

Campbell says TerraX acknowledges that Giant was a problem, and so doesn’t dance around the subject. Towards the end of its operating life, the mine had become more efficient and was better at handling effluent and stacking from the furnace. Both mines, Con and Giant, built Yellowknife, and are still, a dozen years after closing, contributing to the economy through the clean-up efforts.

“But we won’t be operating that way,” Campbell says. “No one does anymore. One of our goals is to try educating people about how industry works today.”

To that end, TerraX has had as many as 700 community engagements according to David Connelly, who has been consulting to Campbell on community and government relations. While some of those engagements may have been as simple as preparing an email to a community stakeholder, others involve community meetings, which can take days to organize. “We have to communicate the impact of our activities with aboriginal communities and thousands of recreational users from Yellowknife. As well there are the utility companies we talk to about issues like hydro lines, telephone lines, micro-towers, and power corridors,” Connelly

says. “We have had community meals and meetings, and formal round table discussions. We have had to seek information from archives and traditional knowledge experts. It’s a huge undertaking.”

There are also the benefits that community stakeholders expect to learn about. This is difficult because it may be a few years before TerraX can estimate the size of a mine it can economically build, although the hope is it will be a large, multi-generational operation serving the Yellowknife area for decades to come.

“We are in early exploration stages and can’t go into First Nation communities with big promises of economic activity and jobs because we don’t know yet,” says Campbell. “We are trying to do the best we can and hire locally whenever we can. It’s easier for us to hire locally. But we’ve been very clear we can’t be a panacea for all local problems. We can’t solve all unemployment issues.”

For now the TerraX site, which they have renamed Yellowknife City Gold Project, is almost pristine. This past winter a drill program was completed so there is some evidence of activity.

“You might see a few cut trees, might recognize where the drill made a hole,” says Campbell.

“There is very little disturbance on the site. Our work ethic as an operator is to live by the letter of our permit and even go beyond those requirements.

“Our philosophy is to keep people well-informed of what we’re doing and what our obligations are with our leases. We’re willing to listen and we’re trying to do the right things for safety and the environment. We want to be open and to allow stakeholders to see what we are doing so they will become comfortable with us.”