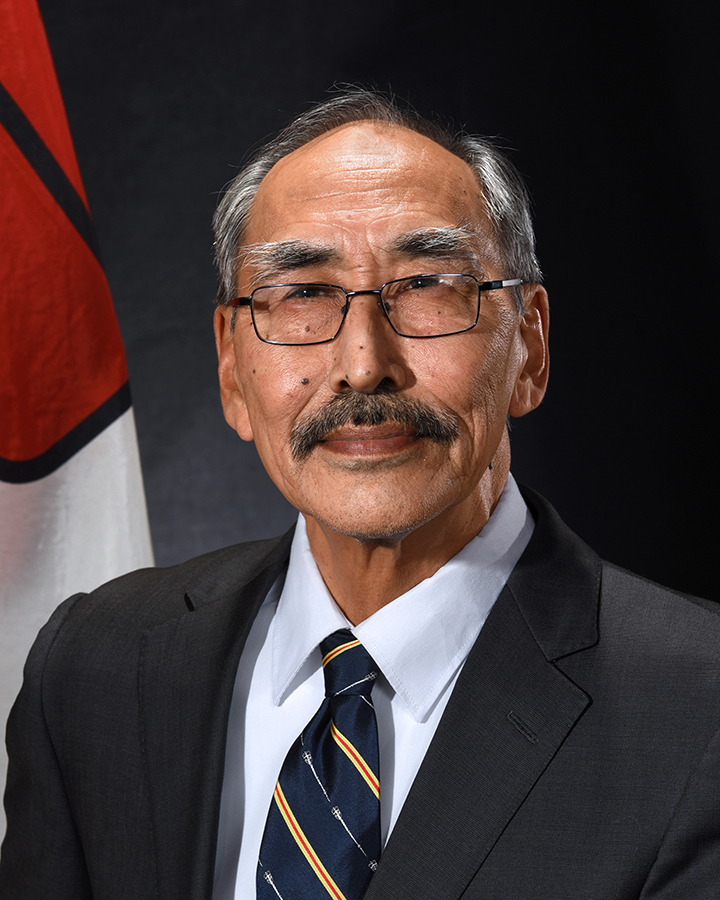

Nunavut’s New Boss

ABQ Goes One-on-One with Premier Paul Quassa

He’s lived on the land, been an apprentice mechanic, interpreter, magazine editor, land claim negotiator, president of Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, education minister, and now the fourth Premier of Nunavut.

Paul Quassa’s life hasn’t always been easy or moved in a straight line, but now this self-described former radical is the leader of Canada’s youngest territory. Aboriginal Business Quarterly connected with him not long after his selection to the top job in Nunavut’s consensus-style government to learn about his leadership style and the experiences that have shaped his life to date.

Our interview is presented in a Question and Answer format to give readers an unfiltered look at who he really is and the approach he’ll take representing the interests of Nunavummiut over his next four years in office.

ABQ:Let’s start at the beginning. I know you were born in an igloo at Manitok. What was life like in those early formative years? What specific memories do you still carry with you now? How do you feel it has shaped you and your leadership style today?

Premier Quassa:

The first thing that comes to mind is that it was a very traditional way of living, where we had a leader in our camp. The leader in our camp was my uncle. A leader in those days was one who provided food to the camp, directed the hunters, and made sure that everyone was adequately fed and well-clothed in traditional clothing like seal skins and furs. We moved from one location to another depending on the seasons, and also on the direction and experience of our leader.

In those days, a leader was not an elected person, but rather, someone who people respected and whose advice and experience was valued and respected. In those days, no one had names or titles, they were just uncles, aunts, cousins. Growing up, I didn’t even know the name of my parents – I just called them ataata and anaana.

That’s the type of leadership that I grew up in; a type of leadership where Inuit values were respected, and people worked together. It didn’t matter what your title was – everyone worked together to provide for your community. I still believe in that today.

ABQ: What was your first job in the wage economy? What was it like in terms of daily tasks? How did it make you feel to be earning a paycheque for the first time?

PQ: When the Co-op was being formed in Igloolik, they had to go down to Hall Beach to acquire some buildings for a store. My first job was to disassemble the building that was to going to be brought up to Igloolik. We worked for about two weeks that summer, and after those two weeks we got $20. In those days, wow, $20 was huge! We celebrated by buying some things from Hudson’s Bay Company that we could never get, like ball caps or things like chocolate bars and chewing gum.

ABQ: You’ve been described by many as a life-long politician. How did you first discover this path and when did you realize this was something you were well suited for in terms of making it your career?

PQ: After I completed Grade 12, I became an apprentice mechanic. One day, I got a long distance call at the garage I worked at from my friend William Tagoona, who lived in Ottawa. I ran to the phone, not knowing who it was. It was William and he said: “How would you like to work for ITC – Inuit Taparitsat of Canada?” He asked me if I was interested and right away, I said yes. I don’t think I was born to be a mechanic.

That was the first time I started working for a political organization. I started as an interpreter, and moved on to being the information officer and then assistant director of land claims. This was in 1974-75. I remember when I was their information officer, I was an editor of their magazine Inuktitut. I noticed I was only sending out 50 copies of the publication to communities in the NWT at that time. This was a magazine to update Inuit on all of the national discussions and meetings around potential land claim agreements. And we were only publishing 50 copies! I was shocked. So I wrote to our president at the time, and asked why we were only printing so few magazines when I knew there were easily hundreds if not thousands of Inuit who would love to read it. A week later, I got a letter back that essentially told me never to question the president again about how many copies they printed. I thought to myself that if I was an Inuit leader, every person would have information that matters to them. That was the moment I decided I would be a leader, and I’ve never looked back.

ABQ: I’ve spoken to many land claims negotiators over the years who’ve told me about the pressure they felt representing their people on such an important stage. How long were you involved in the process and how did it make you feel both during and afterward?

PQ: It was about 10 years after that, in 1985, that I joined the Nunavut Land Claims negotiating team. In fact, I started working at the same time as Paul Okalik. I didn’t know at that time that it was going to be a hectic, demanding, very stressful type of job. All I knew is that it needed to be done, and we had to do it. There were times when we started out that we used a lot of swear words when we got stressed out. It was a lot of pressure. You knew then you were negotiating for Inuit who had never had the opportunity to talk back to the federal government. We were their voices. In those days, Inuit were very meek and just did what the government told them to do. Times were changing. We were radicals at that time, who dared speak out for the things that Inuit always wanted to say. Like the revolutionaries who are the first ones to challenge a government.

ABQ: Can you recall any specific anecdotes from those talks which resulted in the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement where you scratched your head and said this is crazy, why am I doing this? How did you overcome those challenges?

PQ: The most important part was when we realized that under the federal land claims policy of the time, we had to surrender certain rights in order to get the things we had negotiated. That was the hardest part. We said at the time: I am a Canadian – how can I give up my rights in order to gain a government? No other Canadian would ever give up their rights, but we as Inuit had to. That was the hardest part for me, on the negotiating team. It was a head scratcher. On the other hand, we knew that Inuit wanted their own government, so we had to find a balance.

When we went out to do our ratification tour to all of the communities, a lot of Inuit couldn’t understand why we would have to surrender certain rights or titles for lands and waters that we had always used. Elders scratched their heads, too. They said: “Why are we fighting for land that we have occupied for time immemorial? How can we say ‘we want our land back’ when we’ve always had it there for us to use?” They were the hardest elements of the negotiations to make understood, because elders couldn’t understand the concept of land ownership. That’s not an Inuit way of thinking. We don’t own the land – the land owns us.

There were a lot of benefits that came out of the land claim, like how to create, run and own your own business. Learning how to do things on your own. It was all about economic development. Self-sufficiency. It had always seemed like Inuit were relying on government, but this was a way that Inuit could start doing things on their own. It didn’t have to be led by government or qallunaat – it would be decided upon by Inuit, for Inuit. Inuit have always been self-sufficient, reliant on their own skills and abilities. The land claim was about independence.

ABQ: When you’re not working what is your home-life like? What specific recreational activities you enjoy when your schedule permits?

PQ: One time, I took a whole year off of politics, and I lived on the land. That’s the type of life I always wanted to have, but I never had the opportunity. From the age of 6, I started going to school, and I didn’t have a chance to learn the real, traditional way of living. As a kid, I used to envy the people who didn’t go to school because they knew so much more about wildlife and the land than I did. So as an adult – and after I completed my education – I lived on the land for one year. It was refreshing. That’s always something I want to regain again.

ABQ: All successful people have role models they look up to – who are the key figures in your life story?

PQ: I’ll go back to the days when I was an editor for ITC. I got in trouble for trying to say that we have to be more representative in the work that we do, and that’s when I said: I’m going to be a leader someday. That day came when I was president of Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporation (NTI). Now I have a chance to do it again as Premier of Nunavut, but this time to represent not just Inuit, but all Nunavummiut.

I want to be a leader who is compassionate, listens, is understanding and that people also understand in both my actions and my language. Whenever I go to Igloolik, there’s an elder who reminds me that when I was young, I had a hard life. The elder says: “If you were spoiled or favoured, you might lead in a more selfish way.” My life wasn’t easy, so that helps me relate, and be more relatable to people. Life’s too important to be negative or greedy. You have to be positive and giving. And when you approach life and leadership that way, it produces positive results.

ABQ: The last government was truly a champion of sustainable, responsible resource development in the territory. What are your feelings on the subject and are there opportunities in this area that you are excited about for Nunavummiut moving forward?

PQ: We work for Nunavummiut, in the best interests of this land and our future. At the end of the day, we all want to ensure strong, healthy and successful Nunavummiut. And while resource development is a key part of our economic success, we have to also focus on our social development as well. Nunavut has many social challenges – housing shortages, food insecurity, poverty and addictions. Our greatest successes will be achieved when we invest in the health and well-being of our people and our communities.

I always say: We hear so many negative things about Nunavut – the highest rate of this, or that. What kind of message does that send to our youth, who need to be challenged and supported, instead of being left feeling defeated by this negativity? We need to have a more positive outlook on our territory and our people. Social development – making this a healthy society for everyone. We have to be encouraging and have confidence in our current and future generations to succeed.

ABQ: I’ve seen you talk about building strong partnerships with the territory’s Inuit organizations. The Government of Nunavut previously partnered with the Kitikmeot Inuit Association to propose the Grays Bay Road and Port project, which is now in the early stages of moving through the Nunavut Impact Review Board’s process. Sometimes when Northern governments change, their focus changes, too. Is this transformative piece of infrastructure and the landmark partnership behind it still something you personally believe in and what value would you place on seeing it through to completion?

PQ: We want all of Canada to understand the uniqueness of Nunavut, and the need for infrastructure and connectivity. When I met with our regional Inuit organizations, we agreed that we have to work together if we want to see big projects like Grays Bay Road or a Nunavut-Manitoba hydro line to be successful. Governments can’t do it on their own, but when we work together, we can accomplish so much more. It’s like the traditional Inuit values – you can’t survive on the land on your own; you always need a partner. That’s the core of survival. And those traditional values are still important today.

ABQ: Are there other items on your personal to do list that you will push for as Premier?

PQ: As I said before, we need strong partnerships to make this happen, particularly with our Inuit organizations. The Government of Nunavut is a public government who serves all Nunavummiut, but 85 per cent of our public are Inuit, so we often have overlapping responsibilities. At the end of the day, we are all working to make Nunavut a better place for all Nunavummiut.

I want Nunavut to be a place that is vibrant, prepared for the workforce, truly bilingual, has development that enhances employment and is focused on positive ways of thinking. One of my personal wishes is to see a stronger, more prominent use of Inuktut in our territory, and particularly in our public service and government. Our newly elected Cabinet Ministers are all bilingual in Inuktut and English. This is a first for our elected government. I would like to see our public service also adopt more use of Inuktut in their day-to-day operations, starting with Inuktut training for all staff, and making the use of Inuktut more prominent in our workplaces. I always envy other circumpolar countries like Greenland for their retention and promotion of their Indigenous language. There, you see everything in Greenlandic, even labels at the grocery store. You see country food in grocery stores. Everyone’s talking Greenlandic on the streets. They even have Coca-Cola in Greenlandic. These kinds of little things matter. That shows me a society who has kept their language alive and vibrant. That was the vision when we negotiated the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. I’d love to someday see that in Nunavut, too. ABQ