critical coastal

CONNECTION

Yellowknife Might Need Grays Bay Project As Much As Nunavut

The on-again, off-again saga that is the proposed Grays Bay Road and Port (GBRP) project is again back in favour with the Government of Nunavut and that’s something Yellowknifers and local businesses should celebrate.

The project is the brainchild of a landmark partnership between the Kitikmeot Inuit Association (KIA) and the Government of Nunavut, and if it comes to fruition would result in the first highway built in the history of Nunavut.

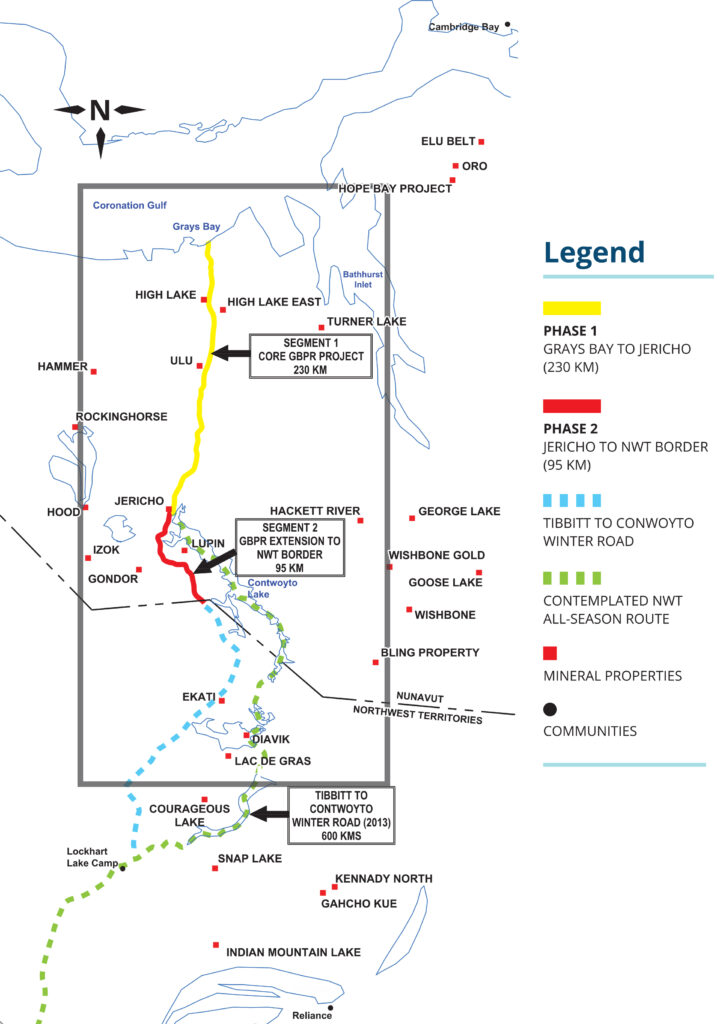

The GBRP project would see the mineral-rich Slave Geological Province, which straddles Nunavut and the NWT, connected to Arctic shipping routes via a 232-km all-season gravel road and a deep-water port at Grays Bay on the Coronation Gulf to the North. The Port would be approximately 830 km north of Yellowknife via the resulting overland route.

“This is an historic moment in the relationship between an indigenous group the Crown,” said Patrick Duxbury, Advisor and Operations Support for the Nunavut Resources Corporation (NRC).

The NRC is an Inuit-owned corporation founded in 2010 by the Kitikmeot Inuit Association to diversify and develop the economy of Nunavut by attracting investment capital to the region.

“Given the timing, it could come at a time 10 years from now when the NWT is running out of diamond mines”

“Inuit are not passive junior partners in this enterprise but are rather co-proponents and joint developers with the Government of Nunavut in pushing this project forward within the federal government and within the private sector.”

Construction is expected to run throughout the year over a four-year period. “In addition to the road and port, the project will require construction of bridges and culverts, quarries, tanks for storing diesel fuel, a runway, a rest station at Jericho Mine and other facilities needed to operate a port, such as a landfill, camp, power supply and sewage treatment,” wrote Paul Emingak, KIA’s executive director, in the proponents’ official submission to the Nunavut Impact Review Board (NIRB).

A project of this scale obviously wouldn’t come cheap and current estimates for the GBRP are pegged at $487.5 million. This includes final planning, engineering and environmental studies at $12.5 million; general mobilization and demobilization at $39 million; materials and supplies at $65 million; on-site work $286 million; and a contingency of $85 million.

“This may also be expressed as the road will cost an estimated $400 million and the port $87.5 million,” explained Jim Stevens, Nunavut’s Assistant Deputy Minister of Transportation.

NWT Wants to Connect

To the south, the GNWT is championing a sister project known as the Slave Geological Province Corridor (SGPC), which would support road access, hydro transmission lines and communications infrastructure into the same areas of significant mineral potential from the south and provide a link for the GBRP to the rest of Canada with a year-round overland route in place of Tibbitt-Contwoyto Winter Road.

The proposed two-lane gravel highway would be approximately 413 km in length and is estimated to cost about $1.1 billion. While that sounds expensive, keep in mind that the historic value of production (in 2018 dollars) from mines within the 213,000-sq-km Slave Geological Province is $45 billion. Completing both the GBRP and the SGPC would help the North adapt to the increasing challenges of climate change by replacing winter roads with more reliable access. It would also mean improved access and reduced operating costs for existing mines, and facilitate resource exploration and development activities throughout the region. All-weather access would also support a green economy by enabling development of the Taltson Hydro Expansion and Transmission Line project and it would enable the extraction of base and precious metals required for low-carbon technologies. Perhaps not quite as advanced as our neighbours’ portion of the contemplated route, the NWT corridor providing the greatest economic benefit has already been identified, based on the results of mineral potential and routing options studies and analysis, and a financing business case analysis is underway.

While an initial project submission under Transport Canada’s National Trade Corridors Fund was not accepted, the GNWT has resubmitted the project under a Northern-specific call for proposals. Five development phases have been identified: Environmental and Planning Studies; Replacement of the Frank Channel Bridge; Highway 4 to Lockhart Lake; Lockhart to Lac de Gras (diamond mines); and, Lac de Gras to the NWT/Nunavut border. Next steps include engaging with Indigenous governments, NWT residents, and other stakeholders, completing a business case and further planning.

What’s in it for Yellowknife?

Impact Economics is an economic research firm based in the NWT capital owned and operated by Graeme Clinton. It has conducted much of the forecasting and modeling work surrounding the GBRP project. He says while it would be virtually impossible to predict what the precise economic benefit of either project would be for Yellowknife specifically, the result would certainly be positive.

There would be many opportunities for jobs and contracts, but it would come down to the available work force and business sector and their ability to supply what’s needed, when it’s needed, at a competitive price.

“In the case of the GBRP, existing relationships with the Kitikmeot region will certainly play a part,” he said. “Nuna, for example, is definitely going to be busy when this goes ahead.”

Clinton’s previous work does demonstrate that constructing the GBRP would boost Canada’s gross domestic product (GDP) through infrastructure-induced Northern resource development – just the development of MMG Canada’s Izok Corridor Project, in concert with construction of GBRP infrastructure will, over a 15-year period, raise Nunavut’s GDP by a total of $5.1 billion and Canada’s by $7.6 billion.

“Beyond the Izok project, with the NWT continuing to push for the southern portion of the route there is the potential for Yellowknife to have a year-round connection to the Arctic Coast and all of the opportunities that fall out downstream from that,” said Clinton.

Not including Izok Lake, the Slave Geological Province (SGP) has significant untapped mineral potential including several defined large base metal deposits (e.g. Hackett River at 82 million tonnes) and hundreds of base metal and gold showings (372 along current proposed route alone). The three diamond mines (Ekati, Diavik and Gahcho Kué) produced 20 million carats, $2 billion in revenue and employed over 3,000 people (FTE) in 2017 and contribute $1.1 billion to GDP directly, representing 28 per cent of the NWT economy.

Clinton said the existing mines and their current anticipated lifespan really highlight why Yellowknife and the NWT should be supporting the GBRP and SGPC projects.

“Given the timing, it could come at a time 10 years from now when the NWT is running out of diamond mines,” he concluded. The lack of infrastructure is consistently cited as a major impediment to exploration and development in the region. In a 2016 study of relative mining costs, Schodde determined that costs for mining projects are 40 per cent to 170 per cent higher in the NWT than in southern regions of Canada. The NWT and NU Chamber of Mines (2018) suggests that capital expenditures can be 2.5 times higher in the North and that exploration expenditures can be six times higher.

The SGPC would open up access for development of small base metal and gold deposits such as those in the Cameron River Beaulieu River Greenstone belt (e.g. Sunrise deposit 4 million tonnes) along with large, lower grade gold deposits (e.g. Courageous Lake – over $15 billion in situ resources). A firm commitment to the SGPC would extend existing mine life and drive an immediate increase in exploration activity along the proposed route.

Strong Support Nationally

The Canadian Chamber of Commerce has already passed a motion of support calling on the government to advance the project after the Yellowknife Chamber, as part of the Territorial Policy Committee, helped champion a policy resolution at the national group’s 89th Annual Meeting last year in Thunder Bay, Ont.

“Each resolution, once approved by a convention, has an effective lifespan of three years and is brought to the attention of appropriate federal government officials and other bodies to whom the recommendations are directed,” said Yellowknife Chamber President Kyle Thomas. “In the case of this resolution, we called on the federal government to immediately fund the GBRP to the tune of $19.46 million, 75 per cent of the overall cost needed to get the project to the point that it is shovel ready.”

The Canadian Chamber also pushed for the feds to recognize the national importance of the project and providing federal support for the remaining $529 million in capital costs.

“Sources for the capital needed could include the Canada Infrastructure Bank, existing infrastructure programs or one-time contributions,” said Thomas. “The Canadian Chamber certainly recognizes the value of investing in Northern infrastructure, it’s good to have that kind of support when going to Ottawa with this size of a request.”

For most Northerners, the biggest boost from building the Grays Bay Road and Port (GBRP) would likely come in the form of long-term, stable good-paying jobs. The exact number of employees required to build and operate the road and port is actively being reviewed by the project partners.

Earlier MMG estimates on the GBRP and its Izok Corridor mineral projects would create 1,140 jobs during construction and some 710 jobs during production using a fly-in, fly-out rotational workforce. The GN is still working on GBRP-specific numbers, but it’s safe to say if the road goes ahead, a flurry of activity would likely ensue.

Although currently stalled due to poor economics, MMG Canada’s Izok Corridor project includes the Izok and High Lake deposits located along the proposed route of the road. Izok is a rich zinc/copper deposit with a mineral resource of 15 million tonnes at 13 per cent zinc and 2.3 per cent copper. The High Lake deposit, located north of Izok, has a mineral resource of 14 million tonnes at 3.8 per cent zinc and 2.5 per cent copper.

“MMG believes that the advancement of the Grays Bay Road and Port Project would help to improve the economics of the Izok Corridor Project,” said Sahba Safavi, President of MMG Canada. “The primary challenge for the project is the substantial infrastructure required to develop this project in Nunavut. There is a large infrastructure deficit in Nunavut, as well as the cost premium for any capital projects taking place in the North.”

Safavi concluded that there are many potential long-term benefits of the link to tidewater at the Coronation Gulf. “[It] could be very substantial and deliver economic and social benefits in the North that stretch well beyond the scope of the Izok Corridor Project and be available to public and private sector interests other than MMG.”

Building the GBRP is predicted to yield a wide range of benefits to Nunavut residents and other Canadians, including:

• Boosting Canada’s gross domestic product (GDP) through infrastructure-induced Northern resource development – just the development of MMG Canada’s Izok Corridor Project, in concert with the construction of GBRP infrastructure will, over a 15-year period, raise Nunavut’s GDP by a total of $5.1 billion and Canada’s by $7.6 billion;

• Stimulating new mineral exploration and development activity in the resource-rich Slave Geological Province;

• Supporting the economies of the NWT, Alberta and other jurisdictions that have extensive business relations with western Nunavut;

• Generating significant amounts of employment for Northern residents in a region that currently suffers from high unemployment;

• Strengthening Northern sovereignty, safety, and security;

• Providing access to infrastructure for federal government departments and the Canadian Armed Forces;

• Connecting Nunavut to the rest of Canada and the world;

• Providing Nunavut communities with access to goods and services from the NWT and beyond via a new overland route;

• Improving food security and reducing the cost of living in western Nunavut communities;

• Providing cost-effective and climate change resilient transportation options for diamond mines in the Northwest Territories – potentially extending the operating lives of these economically-important projects; and,

• Connecting Yellowknife with shorter access to tidewater and commercial shipping routes.