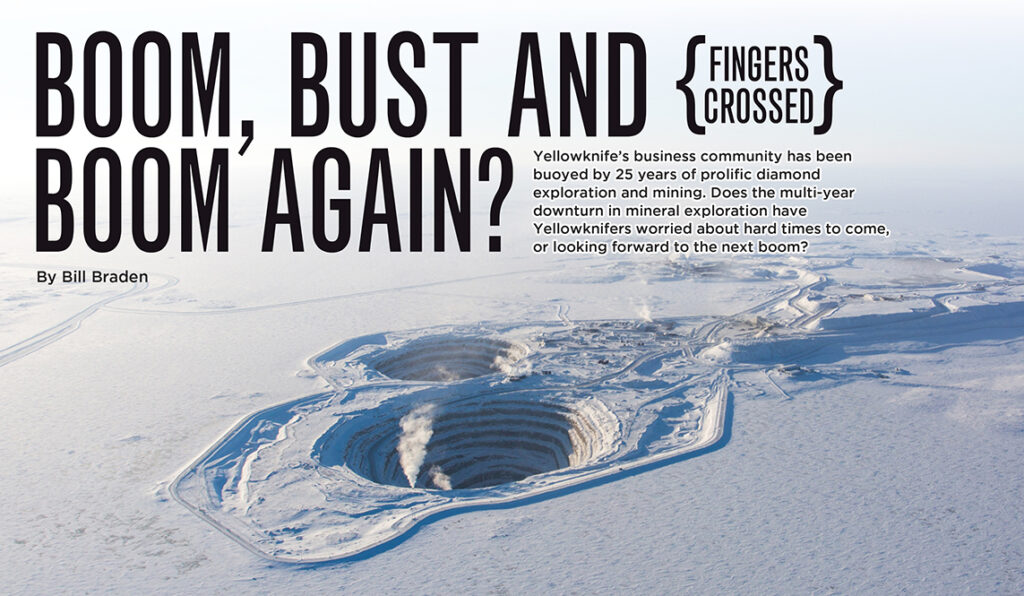

Boom, Bust and ( Fingers crossed ) Boom Again?

When word broke in 1991 that a gravelly outcrop way up in the barrenlands held a treasure trove of diamonds, it wafted virtually unnoticed over Yellowknife’s business sector. This is a gold-mining town. Diamonds? Nah. The savvy local mining guys knew better, but they were too busy staking up an area that would soon be bigger than France to tell anyone. And almost overnight, a new breed of miner was in town, chatting in unusual Belgian, Australian and South African accents, bankrolled by equally unfamiliar companies with names like BHP Minerals (now BHP Billiton), Rio Tinto, and De Beers. That was 25 years ago. What a difference a quarter century makes. With the closure of the Con gold mine in 2003, Yellowknife shed its 65-year long heritage of gold mining and fully embraced – many will say “was rescued by” – the diamond industry. The rich diamond deposits in the Northwest Territories have ranked Canada third in global production, and Yellowknife calls itself the Diamond Capital of North America.

So what does this mean to the Yellowknife economy, and its hundreds of business owners? It really comes down to the spending power generated by these big economic engines, and how successful Yellowknifers are at capturing the opportunities. With the Ekati and Diavik mines, and the Gahcho Kué project coming on stream later in 2016, Yellowknife’s financial picture will be enhanced with these numbers: between 900 and 1,000 mine employees, resident in Yellowknife, with average annual earnings of about $100,000, for a total payroll of approximately $100 million (estimates from GNWT, Statistics Canada and company data, 2011 to 2016.) Ekati, now owned by Dominion Diamond, directly employs some 630 resident workers. Diavik reports that it counts 227 resident workers of its total workforce, plus another 84 contract employees. Gahcho Kué will be in production by late 2016, with an estimated total workforce of 400. Alongside those well-paid jobs (2011 average $96,384) is the indirect labour force impact in the supply and service sector. The GNWT estimates that for every direct mining job, 1.5 more are created in every market sector from trucking to aviation to office supplies.

Woven into this story is the massive capital cost of building these mines in one of the world’s most remote regions. At roughly $1 billion each (and in the case of the Gahcho Kué project, some 700 workers) these projects gave a much-needed jolt to the North’s economy. The picture gets very clear that the discovery of diamonds was indeed a remarkable rescue with a solid future. Several Yellowknife businesses, small, and home-grown, shared their stories of growth and diversification in the diamond era – or some cases, not so much.

BBEX: By land, air, ice and sea

From their start 40 years ago in a backyard shed on Ragged Ass Road, Max Braden and the late Rick Burry started Braden Burry Expediting and quickly built a solid reputation serving remote green-field exploration camps from the Alberta-NWT border to the Arctic Islands. Successive owners seized the opportunities created by the expanding international scope of mining the NWT. They broadened into logistics, specializing in remote locations, and now have bases in six NWT and Nunavut centres plus Edmonton, Winnipeg and Ottawa. Rebranded as BBEX, it became a NorTerra company owned by the Inuvialuit Development Corporation of Inuvik since 2007.

Sean Grey, BBEX’s vice-president of business development, says the company was involved in many of the North’s major discoveries. “As the mines grew, so did BBEX in scale, locations and our systems, tied to a diversification strategy started more than a decade ago, ” says Grey. “In Yellowknife specifically, we are highly reliant on the mining that is supported from Yellowknife, more so than our other operations.” Experience and knowledge gained from servicing the northern mining industry allowed BBEX take the next steps to expand its business. “BBEX has been fortunate and positioned well in a way that’s allowed the company to take the lessons we’ve learned from working for mining clients and apply them to other industries in the north and across Canada,” says Grey. That’s recently been enhanced with strategic alliances with international freighters Air China, Air France and KLM. With diversification into other markets, BBEX now counts its directly-generated mining business at less than 25 per cent of revenues, Grey says. The eventual sunsetting of the original diamond mines will have a severe economic impact on the region, says Grey. “But over four decades we, as have other northern businesses, learned to evolve between the cycles in the mineral exploration and extraction industries. As a strategy in the region, we see opportunity and our responsibility to work together to make new developments feasible.”

MATCO: Evolving with the miners

Started in Norman Wells as a small business in 1966 when owners Lloyd and Ray Anderson saw an opportunity with the area’s booming oil and gas sector, MATCO (Mid-Arctic Transportation Company) was one of the first land-based transportation companies to serve the Sahtu. It now has eight locations in the N.W.T., Alberta and the Yukon. In 2013, Northern American mover Manitoulin Transport acquired MATCO. Leon Johnson, MATCO’s corporate, commercial and international sales manager, credits the diamond era as a major catalyst for the company’s growth. “Yes, the mining industry, in particular in Yellowknife, the diamond mines, have absolutely spurred additional moving business for our company. We have benefitted in local, domestic, cross-border, commercial and international activity and relocations.”

Doing business with international clients has upped the game for many northern suppliers in their own safety, equipment and organizational standards. MATCO is no exception, says Johnson. “There were multiple aspects that were required in order to elevate our services to meet their (international clients’) relocation, human resources, ISO and safety standards.” “The mining industry and diamond mines in particular have been a major customer of ours over the last 20 years and we hope that continues as we move into our next 50 years of business,” he says.

INKIT: Custom treatment always works

“We do business for the mines, and companies that work for the mines. They’re interwoven into all kinds of businesses,” says Dawna Marriott, president and project manager for Inkit, a design and advertising firm that’s marking 36 years in business. Marriott says that while Inkit has not specifically tailored its services to attract business from the mines, all of the work Inkit does is custom, tailored to the needs of the specific client. “We do a lot of work for Diavik and we’ve developed a really good working relationship with them,” she says. “… we know what they expect and we give them what they need. There’s that trust there because we work with them so much. It would be like that with any client.” She’s found the big miners want to give northern entrepreneurs a fair chance at their business. “If you provide good service, good quality and competitive prices – obviously it will often be a little bit more expensive than the south – but if you do good work they tend to try to work with northern companies.”

OFFICE COMPLIMENTS: Mining’s not a big player

Judy Murdoch is business manager with Office Compliments, a familiar name in business circles in Yellowknife since 1986, supplying temporary office support and services. Murdoch says while the overall economy has enjoyed the diamond era, it has not made a big addition to OC’s bottom line for several years. And she’s okay with that. Noting that the large companies all have their own human resources departments and staffing resources, she says they have only occasional need for the services OC can provide. “We do provide temporary staff on request, but it’s not a large percentage. In a few cases, the placements we have made with them have resulted in those people going to full time positions.” That’s a good thing for the worker, but it reflects the chronic strain put on a lot of small businesses that can’t match the relatively generous pay packets offered by gov ernment and other big employers.

SUB ARCTIC SURVEYS: Built on the diamond surge

“It was a very big impact. It put us on the map,” says Bruce Hewlko, president, and with his wife Sonja, owner of Sub Arctic Surveys Ltd., of the diamond staking rush in the early 1990s. With ties to the legendary Arctic surveyor John Anderson Thompson, the Hewlkos started Sub Arctic in 1992, by happy coincidence right on the cusp of the diamond exploration boom. “We started working with BHP Billiton in the winter of 1994. And Diavik and Aber in 1994 when they made their first discovery. It carried through to about 2003 with Snap Lake and Gahcho Kué,” he recalls. He

wlko scrambled to keep up with the demand, at peak season having close to 30 of his 45-person workforce dedicated to mining, and in particular, exploration surveys. But since 2003, it’s a very different story: from 50 per cent of demand for surveying services coming from mining and exploration, it’s plummeted to five percent. “There’s no exploration projects on the go, very little mineral claim staking requiring surveying. And the small operators don’t have any money. The crash in exploration has had a big impact of the bottom line for SAS,” says Hewlko.

Hewlko has re-tooled the business to construction surveying and still keeps a seasonal team of up to 25 employed, several of them in the company’s satellite office in Iqaluit, set up three years ago. But he laments the dearth of exploration and its impact on those local businesses that relied almost entirely on it. “It’s changed a lot from a mining town to an administrative town. There’s a bit of different feel in the community. We’ve adapted, but others, specifically made for exploration, are really hurting.” Hewlko has hit on what is universally seen as the NWT economy’s Achilles heel: that without robust exploration today, we’re in danger of not replacing our huge reliance on diamond mining as and when its sparkle dims and dies. That won’t be for some time, at least on the horizon that most small businesses watch. Ekati, with its recently green-lighted Jay Pipe expansion, could be producing until 2030. Diavik has affirmed it will be mining until at least 2023, and then will be involved in reclamation for several years after that. And the De Beers-owned Gahcho Kué project, set to go into full production by late 2016, has at least an 11-year life.

Some advanced exploration does continue, notably Kennady Diamonds Inc. exploration play next door to Gahcho Kué, and a number other small explorers in the same region, but the days of a healthy, diversified prospecting climate have been drastically diminished across the North since 2009. But there are two projects now underway in Yellowknife that will keep the local mining dollar pulsing. On Yellowknife’s doorstep is the TerraX Minerals Inc. program to explore ground neighbouring both the Giant and Con works. TerraX’s president Joe Campbell is proving again the old maxim about gold mining: your new mine is probably next door to the old one. Terrax has been methodically re-sampling ground just north of the Giant mine since 2013 and is finding impressive grades. TerraX is years away yet from confirming a viable deposit, but has captured the attention of senior investors in the potential for new gold in the Yellowknife Greenstone district. “TerraX has put between $2 million and $5 million per year into the Yellowknife economy over the last three years,” says Campbell, “made up of services, supplies, consumables and labour. Our expenditures have increased every year since inception of the project.”

Campbell cautions that exploration spending is linked to investment spending, something that’s “highly variable” on the junior exploration market. But it is running drilling and ground geophysical programs almost year-round, employing approximately 30 people, and later this year plans to open a permanent office in the city. The other big mining-related project Yellowknife contractors are anticipating is the closure of the sprawling Giant mine site, which shut down in 2004. In its 56 years of operations, the Giant mine yielded seven million ounces of gold, but left behind a toxic mess that will cost taxpayers about $1 billion and a decade to remediate. Sharon Nelson, senior communications advisor with Public Works and Government Services Canada, says a main contractor for the work has yet to selected, but the construction management deal will likely be worth between $600 and $700 million. “The percentage spent locally cannot be determined at this time. However, efforts to provide opportunities locally are being made,” says Nelson, adding that work packages will be tendered giving local businesses the chance to be involved. While the premature shutdown of the Snap Lake Mine by owner De Beers late in 2015 was not entirely a surprise, it rattled Yellowknife. It was a sudden wake-up call to the reality that any resource-based economy is never rock-solid. Current mine plans call for Diavik to begin spooling down in 2022, while Ekati could see 2030 before beginning reclamation activities. Local entrepreneurs aren’t yet anticipating the end of the diamond economy, but they know that day will come. “I don’t think it’s too far out to not think about it,” says Inkit’s Dawna Marriott. It’s too soon to panic about it, but it’s obviously something to keep in mind. You don’t want to tailor yourself just to diamond mines… they won’t be here forever. And it’s going to be [followed by] something else.” “The region and the territory has done well by the investments of the explorers and the miners,” says Leon Johnson of MATCO. “Our decisions and actions now will determine the economic state of affairs in the 2020s and 2030s.” And while the downturn in exploration has put a dent in the survey business, Bruce Hewlko has seen enough cycles – from base metals in the 1970s, to gold, to oil and gas, then diamonds in the 1990s – to know “there’s always something going on.” “I’m always bullish on the North,” says Hewlko. “We’re in a little bit of a lull right now. But there always seems to be something coming on stream.” YKCI